1 Minute read |

In 10 years green bonds have gone from being an esoteric fringe product to being accepted and used in the mainstream of the international capital markets. These instruments are critical in helping to bridge the massive investment gap required to meet the targets set out in the 2016 Paris Agreement on Climate Change and the 2015 UN Sustainable Development Goals (see figure 1). However, there are several concerns which could undermine the credibility and evolution of green bonds as a much-needed market product. These include a surprising lack of green contractual protection for investors, so-called greenwashing, the quality of reporting metrics and transparency, issuer confusion and fatigue, and a perceived lack of pricing incentives for issuers. This article by Baker McKenzie lawyers discusses these concerns and presents potential solutions. |

In the space of barely a decade, green bonds have gone from the periphery of the capital markets to being one of its fastest-growing segments. Green bonds are now used globally as a financing source for a wide range of issuers including green renewable energy companies, sovereigns and supranationals, and brown corporate issuers seeking to transition some or all of their business operations.

Global green bond issuance in 2019 is projected to hit $200 billion (against $167.3 billion in 2018). Green features have also expanded across the asset class from vanilla corporate bonds to project bonds, asset-backed bonds and covered bonds, with 2018 witnessing the first green commercial paper programme. With the Paris Agreement and UN Sustainable Development Goals as the compelling double catalyst, and the UN stating that the world needs $90 trillion in climate investment by 2030 to achieve these, there should be no limit on the rise and use of green bonds.

However, there remain significant challenges and risks to the continued use and growth of the green bond market. These include inadequate green contractual protection for investors, the quality of reporting metrics and transparency, issuer confusion and fatigue, greenwashing, and pricing. We describe these challenges below, and suggest ways in which the green bond market can evolve to safeguard the integrity of the asset class, make the instrument more robust from an investor perspective, and enhance product transparency and discipline for all market participants.

Figure 1: Timeline of major developments in the green bond market |

|

Figure 2: ICMA Green Bond Principles |

|

Common terms and actionable rights

There is no universally accepted legal and commercial definition of a green bond. Imitating the International Capital Market Association's (ICMA) Green Bond Principles, elements common across many standards include: (i) use of proceeds disclosure stating the cash raised will finance new or existing projects that have positive environmental or climate benefits; (ii) ongoing reporting on the foregoing green use of proceeds and (iii) the provision of a second opinion by an independent third party reviewer certifying the green aspects of the bond (see figure 2).

However, the green bond market has developed in such a way that none of the above product-critical elements confer actionable rights on bondholders. This may have been understandable as the product's first steps were relatively non-confrontational (and so easy for issuers to digest) to encourage market growth. But as the market matures, problems have arisen. Use of proceeds, ongoing maintenance or withdrawal of the published (and relied upon) second opinion review and annual reporting are not often included as direct covenants in the terms and conditions of green bonds. Failures to use the bond proceeds for stated green projects (or deliberate use for non-green purposes) and inadequate annual reporting (or simple non-compliance) are accordingly not events of default or put events that would enable the noteholders to accelerate or redeem their bonds in the event of breach. Nor are they step-up events, which trigger an increase in the coupon payable by an issuer. Indeed, risk factors in listed green bonds will often specifically highlight that no event of default or put event will be caused if the use of proceeds or reporting referred to elsewhere in the disclosure document are not complied with. See figure 3 for an example of such language.

This provokes a dilemma. Bondholders who are still being paid interest and principal on time per the terms of the green bonds may be unable to show loss, and so may be unable to have effective redress. A bondholder who is placed in breach of its own investment criteria may be obliged to promptly sell in the secondary market and in so doing may incur a loss. In the absence of express contractual provisions, sustaining a claim for that loss may prove difficult. While clearly there are reputational motivations to dissuade against deliberate mis-selling by issuers, the fact remains that there is no contractual stick to ensure that bonds sold as green remain green for their lifetime. This risks potential abuse, which could severely undermine the credibility of the green bond market. An example of things going badly wrong for investors is the high-profile case of the Mexico Airport green bonds (see figure 4).

Figure 3: Sample risk factor from a green bond prospectus for a bank issuer |

“Although the Issuer may agree at the Issue Date to allocate the net proceeds of the issue of the Green Bonds towards the financing and/or refinancing of Eligible Green Assets in accordance with certain prescribed eligibility criteria as described under the Green Bond Framework of the Bank, it would not be an event of default under the Green Bonds if (i) the Issuer were to fail to comply with such obligations or were to fail to use the proceeds in the manner specified in this Offering Circular and/or (ii) the Second Party Opinion issued in connection with the Green Bonds Framework were to be withdrawn...” |

Figure 4: Mexico Airports: the green bond that wasn't |

|

Reporting standards, metrics and transparency

Green bond reporting is built on two simple pillars: (i) the pre-issuance use of proceeds disclosure (which sits alongside and aligns with the second opinion report) used to sell the green bonds, and (ii) the also disclosed post-issuance ongoing reporting on the actual use of proceeds.

The ICMA Green Bond Principles do not outline what use of proceeds will be considered green. This analysis is left to the issuer, its advisers, and the second opinion reviewer. The current practice is to aver compliance with a rather broad category of published 'eligible green projects', confirmed by the second opinion review as green. The issuer then determines specific usage of the cash proceeds raised. Issuers have their own criteria or definitions of an eligible green project, with varying levels of specificity and detail. This results in maximum room to manoeuvre for the issuer, with the investor then looking to the post-issuance reporting to see what its money was in fact used for. That is rather opaque, and can be a dissuading factor for an investor concerned that the use of proceeds does in fact match with their own investment guidelines. While in June 2019 the EU Commission published a detailed taxonomy for environmentally-sustainable economic activities which will assist issuers in describing their eligible green projects (which will be used in the voluntary, non-legislative EU green bond standard – see the June 2019 EU Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance Report on Green Bond Standard), it remains to be seen whether this will have the intended effect of increasing transparency.

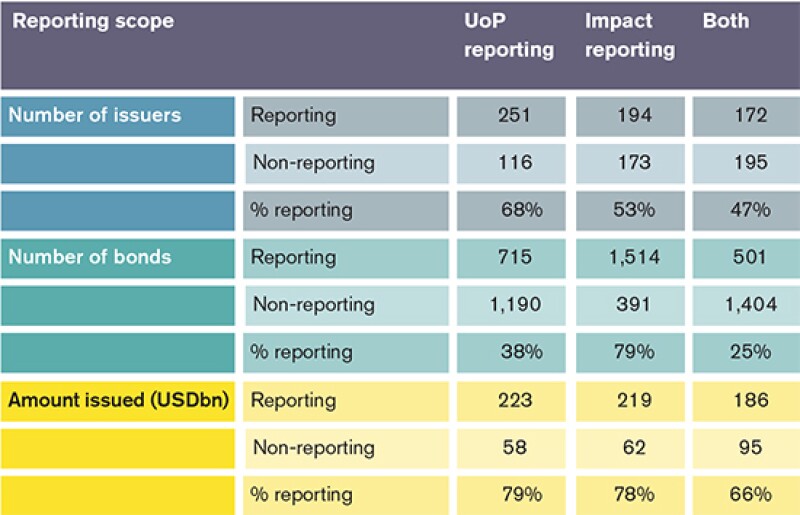

The strength of the second pillar reflects any weakness inherent in the first. While another core limb of the ICMA Green Bond Principles, post-issuance ongoing reporting is not an area free of problems. Market practice on frequency, the actual level of detailed reporting disclosed, and statements of non-compliance all vary. A recent Climate Bond Initiative study (March 2019) found that only 68% of green bonds in their study benefited from regular post-issuance reporting, with only 53% providing reporting on allocation / impact metrics (see figure 5). While these figures are significantly higher when the issuer committed in its pre-issuance disclosure to providing ongoing reporting at a given standard, it nonetheless illustrates the extent of the problem facing this market.

Figure 5: Post-issuance reporting

Source: Climate Bond Initiative Study, March 2019

Greenwashing

Greenwashing, as a concept, refers to the deceptive promotion of the perception that an organisation's products, aims or policies are environmentally friendly. In April 2019, the head of the International Accounting Standards Board stated publicly that "greenwashing is rampant" – and while this was a reference to the corporate environment generally, green bonds are potentially tainted by this. Some bonds are described as green despite not actually following commonly accepted use of proceeds/reporting requirements for green bonds, as outlined above. With no single global standard or recognised legal definition, and the market criteria based on voluntary compliance, it is difficult to conclusively say if some bonds are green or not, or indeed to assess their level of greenness; hence the growing scepticism around the greenness of green bonds. Is a bond green because (a) the issuer asserts compliance with the ICMA Green Bond Principles, (b) it is included in a green bond index and/or (c) it has been confirmed as green by a third party independent second opinion expert review? As described further above, the lack of direct investor protective provisions which make a bond green in the eyes of the market leads to a significant risk of greenwashing or related issues.

Issuer fatigue and confusion

This essentially simple product is seen as overly complex to many issuers given the multiplicity of criteria, the apparently overlapping roles of some market players, and the dizzying and ever-increasing sets of rules, disclosure reporting guidelines and standards with which they may need to comply (stock exchanges, rating agencies, second party reviewers, disclosure reporting guidance, certifiers, index providers, industry bodies such as ICMA and the Climate Bond Initiative and the increasing phalanx of active buyside industry groupings focused on sustainability). Many issuers are confused and fatigued – especially those in the EU which now have the entirely new overlay of the EU action plan and a new EU Green Bond Standard. Faced with this and the lack of demonstrable reward in improved pricing as described below, it is understandable that some issuers opt not to use the product, despite its societal good and manifest public relations advantages.

Pricing benefits of going green?

An increasing amount of institutional investors have clear and established green/sustainable investment guidelines. This will only increase, especially for investors in the EU as buyside-directed regulation (such as reforms of the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive and UCITS Directive proposed by the EU Commission) come into force. This considerable and growing buyside demand has not yet clearly translated into clear pricing differentials for green bonds versus equivalent non-green plain vanilla bonds of the same issuer. Anecdotal market evidence suggests that any such primary market discounts at issuance are marginal at best. There appears to be a premium in the secondary market for green bonds versus equivalent plain vanilla issuer debt – however, this is of little benefit to issuers who need the discount to be applied on the primary sale in order for them to reap any upside. This lack of obvious pricing benefit is not helpful for issuers who are contemplating green bond issuance but are daunted by the new process, the new external parties involved, changes to their regular documentation platform, plus all the related expense.

Improving the product: some core suggestions

Given the urgent imperative of addressing the Paris Agreement limits on global warming, it is our view that much can be done to ensure the ongoing success of green bonds as a product (while not compromising their commercial and financial feasibility). To that end, we would suggest that as flagged above, options to strengthen the green bond market include: (i) incorporating the green use of proceeds and/or reporting provisions directly into the terms and conditions of the bonds, (ii) accordingly making them actionable via an agreed put event (we recognise that a related event of default will be seen as too draconian and face too much resistance) and/ or (iii) introducing margin incentives as a penalty for non-compliance.

Actionable green obligations will be more contractually onerous on issuers, who as highlighted above are already weary of conflicting and overlapping green bond criteria and standards. However, the carrot in exchange for the right of action stick is that the investor community, which is increasingly focused on green and sustainable investments, should reward issuers with increased appetite and therefore lower pricing for such actionable green bonds.

If adopted, such a green bond would not constitute the first time that green provisions were made contractually operative in the sustainable finance space. Green loans more frequently have enforceable green covenants – and a substantial number of green loans reward the borrower with improved margins if the borrower can prove it has met certain objectives linked to green or sustainable principles.

As with any capital markets innovation, prospective corporate issuers may be understandably reluctant to be first movers. But governments, supranationals and sovereign wealth funds (many of whom have already embraced green bond financing) would be ideal role models in incorporating express green provisions in green bond contractual documentation. Professor Rodrigo Olivares-Caminal of Queen Mary University of London notes:

"Public sector entities in many case have longer investment horizons than short-term commercial issuers, often have political or explicit mandates to "do good" as well as achieve commercially viable financing and benefit from connections to policy-makers".

Once one or two such pioneering issuers adopt these new best documentation practices, it is easier for others to adopt them as well – or look less green by comparison.

Product incentivisation

Tax

Given the clear and urgent public policy imperatives issues at play, there has been some discussion of policymakers providing clear tax incentivisation for green bond issuers and/or investors (aside from any tax considerations at the level of the eligible green projects). To date this has not come to fruition in any major jurisdiction, though some related initiatives are extant in Singapore and Malaysia. Interestingly, one argument raised against such tax incentivisation is precisely the fact that bonds which are labelled green do not have any actionable contractual rights ensuring that the proceeds will be applied in the disclosed green fashion. Thus the taxpayer may inadvertently end up subsidising a plain vanilla bond.

This argument is easily surmountable by providing tax incentives only in respect of those bonds with clear actionable green-focused legal terms or, alternatively, by having back-ended tax benefits when the bond is at maturity and its greenness and compliance with its disclosed purpose can be evidenced. This would have the dual effects of bolstering the green bond market and helping to support clear public policy objectives (i.e. practical implementation of the objectives of the Paris Agreement).

Investor risk weighting

Investor-friendly reforms have been posited in the area of bond risk weighting to advantage green bond investors (mimicking that for sovereign bonds). Again, here, advantageous risk weighting could be tied directly to actionable green terms. In the EU this could be implemented via amendments to the Capital Requirements Regulation (Regulation (EU) 575/2013).

Buyside industry and activist groupings

Industry bodies and investor action groups such as Climate Action 100+, as well as large market investors such as sovereign wealth funds and pension funds, are in a strong position to drive development of this market. Investor recognition and the reward of good green corporate citizens would strengthen green bonds as a dynamic capital markets product supporting genuine economic and societal needs.

Next steps

Time is short. Real concerns impacting green bond credibility risk compromising the sustainable finance project more generally, with potentially serious consequences for all. Issuers who readily endorse the Paris Agreement and the UN's 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (and recognise and reap the positive public relations value of doing so) should be bold. This is a dynamic and evolving market. Embracing product innovation and development with increased investor rights, and supporting broader and deeper product incentivisation, works for all. Issuers, investors, underwriters, regulators and governments/policymakers should all be key players in moving the green bond market in this direction. It is in everyone's collective interest.

|

Michael Doran Partner Baker McKenzie, London |

|

|

James Tanner Senior associate Baker McKenzie, London |