When China's new foreign investment law was first drafted back in 2015, the excitement was palpable. Foreign banks have long been able to operate in China, but most have struggled to gain ground over their domestic competitors. This hugely important legislation looked like that could finally change; that everyone could participate in the most remarkable growth story of this lifetime, if they wanted to.

Fast-forward five years and it's a very different story. The details of the law were not revealed until November 2019 – making feedback difficult, to say the least – and a series of unfortunate events, from rapidly-escalating trade tensions with the US to the coronavirus – have overshadowed the grand unveil on January 1.

"Few clients have been moving into mainland China, due in part to the local authorities taking up considerable management time and costs," says UK-based Akin Gump M&A and antitrust partner Davina Garrod.

In-house lawyers agree. "Chinese M&A is down by all metrics, for a couple of reasons," says an M&A lawyer at a UK bank. "More recently, the coronavirus is absolutely going to have an effect on doing business in China. M&A is impossible if you can't actually go to the country."

|

|||

|

Article 3 of the new regulation commits China to the basic state policy of encouraging foreign investors to enter the market. It reads: "The State shall implement policies on high-level investment liberalization [sic] and convenience, establish and improve the mechanism to promote foreign investment, and create a stable, transparent, foreseeable and level-playing market environment." While promising, the new commitments are also vague, and could see acquisitions remain a challenge for international investors.

The new law emphasises equal national treatment for foreign investors. They will also be granted equal protections, as stated in Article 5: "The State shall protect foreign investors' investment, earnings and other legitimate rights and interests within the territory of China in accordance with the law."

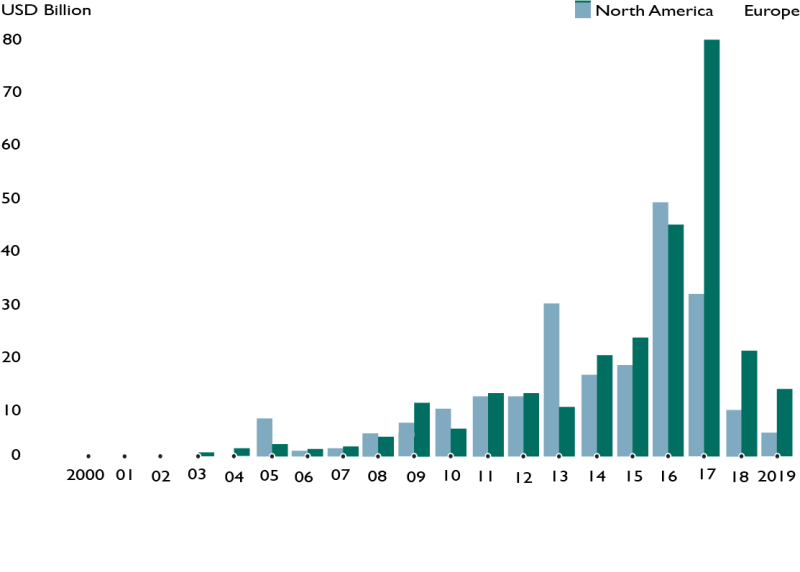

European companies' wariness about entering the Chinese market is reflected in a dip in Chinese investment into Europe. Research by Baker McKenzie shows a fall in Chinese investment into Europe of 40% (comparative to North America at 27%) in 2019. This was the lowest level since 2010, and down 83% from the 2017 peak of $107 billion. Perhaps reflective of the trade war, Europe received more than twice the amount of investment ($13.4 billion) than North America ($5.5 billion).

Baker McKenzie partner Peter Lu says: "The current nature of the relationship between China and the US has resulted in many Chinese corporations directing their investment to the domestic market instead." This has led to increased competition; inevitably many corporations want to be the strongest player on their home turf.

As well as boosting the local economy, this strategy provides an opportunity for Chinese companies to compete domestically before they tackle the European market – which can be highly crowded and competitive. Given the option to expand abroad or strengthen their position at home, Lu says that many would now choose the latter, and in doing so gain invaluable experience within their home territories and boost their chances of success in Europe at a later date. "This is a shrewd decision, as you have to learn to walk before you can run," says Lu.

"The Chinese government wants inbound portfolio investment, and will continue to open avenues to encourage this," says Rory Green, economist at TS Lombard. "There is also the question of relative attractiveness. Trade war uncertainty and the issues surrounding the coronavirus have led to it being a less attractive place for market participants to invest."

Trade wars: Finding a culprit

Hate him or love him, it is hard to deny the impact that the election of Donald Trump as president has had on the relationship between the US and China. In the years following his first imposition of tariffs on China, the swift retaliation, and the significant ramping up of the regulatory regime in place to protect US technology and national security, tensions have escalated to never-before-seen levels.

Between the back and forth of tariffs on imported goods, known the world over as the trade war, and the inclusion of the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (Firrma) into the National Defense Authorization Act in June 2018, it is no surprise that deal flows, investments and trade more broadly between the two countries have all slowed significantly.

Data provided by economic research firm Rhodium Group suggests that foreign direct investment (FDI) into the US from China has fallen by as much as 90% since 2016 – from the lofty heights of $46.5 billion, to a mere $5.4 billion last year. "When I'm in China speaking to corporate clients in the consumer or agriculture sectors I can really feel the pain," says Samson Lo, head of M&A at UBS, Hong Kong SAR. "Consumer industrial companies can really feel it – prices go sky high and goods are less affordable for the general consumer."

FDI is quantifiable. Exactly what is causing it to fall, however, is up for discussion. IFLR put this question to a number of in-house lawyers and dealmakers.

The chairman of the M&A group at another major international bank in Hong Kong SAR says there are a number of factors at play: "The trade war hasn't had as big an impact as other things – the regulatory environment affects valuation levels for M&A, as well as strategy implications like technological disruption. Those things are far more important to M&A volumes and sentiments than the trade war, in my opinion," he says.

The view from private equity is much the same. While the trade war is of course impacting the economy, when it comes to investments and targeted acquisitions it remains only one of the risk components of how a firm would evaluate strategy from a macro perspective. "As we make decisions in the short and medium term about putting capital to work, the noise [around trade wars] is hard to deal with," says a partner at a New York private equity fund. "But it's only one of a range of concerns at this point."

Contract lawyers’ coronavirus solution |

|||

From manufacturing delays to store closures, the impact of the coronavirus has rattled China and all supply chains connected to the country. Many businesses are affected, faced with delays or the failure to fulfil contractual obligations. To date, Chinese buyers of copper and liquefied natural gas have declared force majeure. While force majeure clauses may be relied upon – the Chinese government is encouraging their use – lawyers warn that they may not have been negotiated properly into agreements. If there is a force majeure clause in the contract, it has the power to remove liability for natural and unavoidable catastrophes that interrupt the expected course of events and restrict contractual parties from fulfilling obligations. If there is no force majeure clause in a contract, contractual parties are liable for what they cannot perform even if specific circumstances beyond their control occur. "While force majeure clauses are found in the majority of contracts, in practice, parties to a commercial contract frequently don't spend enough time on the negotiations and drafting of such clauses," says Julien Chaisse, professor of law at the City University of Hong Kong. "There is widespread assumption in the business world that the force majeure risk will not affect parties, or the force majeure clause is a legal necessity and does not impact business risk allocation under the contract."

He continues: "These types of assumptions are widespread, dangerous, and largely wrong. The problem now will be establishing how many force majeure clauses were drafted in recent months and years in the thousands of contracts that regulate trade with Chinese parties." Some contracts will feature clauses that capture the epidemic risk and relieve the parties from performing their contractual obligations. Others will not, meaning parties are obliged to perform their duties. "A third category – probably the most problematic – will only provide for ambiguities, leading to many disputes which will have to be decided by domestic courts and arbitral tribunals," says Chaisse. According to Vivian Mao, partner at Dezan Shira & Associates, if specific circumstances such as epidemics, diseases and plagues have been included in the force majeure clauses under executed contracts, the coronavirus can easily be identified as a force majeure event. If that's not the case, typically arbitrators and courts will judge whether the event falls into force majeure by judging whether the event conforms to the associated characteristics: unpredictability, unavoidability, and insurmountability. The China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT) will play a pivotal role by providing force majeure certificates to companies affected by the virus. However, there are conditions to obtain these certificates. "The ongoing situation in China has understandably resulted in some suppliers being unable to deliver on contracted inputs to their downstream customers, including European companies both in China and abroad," says a spokesperson at the European Chamber of Commerce in China (EUCCC). "In response, the Chinese government has taken the highly unusual step of issuing force majeure certificates to absolve qualifying suppliers of their contractual obligations." The force majeure certificates issued by CCPIT have been recognised by the governments, customs, chambers of commerce and enterprises of more than 200 countries and regions and have relatively strong enforceability. However, whether the force majeure certificates issued by CCPIT will fully or partially exempt the contractual parties' liabilities for breach of contract will depend on a number of factors. "In practice, the epidemic duration, the detailed provisions in contracts, scope of government order, and impact on fulfilment of the contract should be fully considered," says Mao. |

Trade wars: Not just tariffs

Regulations are impacting deal flow between the US and China just as much as, if not more than, the imposed tariffs.

The landscape is highly unusual. On the US side is the beefed-up multi-agency-led Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (Cfius), which is throttling Chinese investment into the US. On the other side, the Chinese government is implementing a number of reforms designed to attract foreign investment – including from the US.

As laid out by Jason Yang, head of corporate and institution coverage for the Americas at ICBC Standard Securities – the largest bank in China – the country and the bank are trying to encourage US clients to enter. "We all know the Chinese economy has slowed, and that confidence between the US and China over the last two years has also slowed," he says.

"But the Chinese regulator has also reduced its bank shareholder limitations, which means US [and other jurisdictions] banks, insurance companies, security firms or others, can hold a majority shareholding in China to acquire majority shares of that institution under a new entity." This implies huge potential for international banks' ability to compete.

Chinese investment volumes in 2019

Source: Baker McKenzie

"If you look at these banking regulations relative to the new foreign investment law, they're much more concrete. They are quite forward and market-leaning in terms of liberalisation," says Harry Broadman, emerging markets practice chair at Berkeley Research Group and former member of Cfius.

"It signals to me that the policymakers regulators in China realise that in order to continue to grow they need other sources of financing from the outside world, not just state-owned banks or the smaller domestic banks in China. It is a helpful change in policy, if it is enforced."

In addition, China's State Administration of Foreign Exchanges (SAFE) has introduced new draft measures that will allow foreign institutional investors to participate in interbank FX derivatives and to manage foreign exchange risk arising from interbank bond investments.

"China has the third-largest stock and bond market in the world – it's hard for us to ignore that. The local market is very significant for an institution to be successful," says Lu Cao.

Internally, China is going through significant, structural economic changes, and as it works through that process there will be ups and downs. Regulators are working to ensure that the country and its financial system progresses as smoothly as possible through that journey.

|

US President Donald Trump’s America First policy has been an obstacle for Chinese authorities |

Trade wars: Just blame Cfius

Like many disputes before it, the ongoing trade war between the US and China is being fought on many fronts. As well as the restrictions and tariffs being imposed on either side, strong regulatory protections have been installed in the US that prevent Chinese investors from acquiring companies that its government deems to be of significant national importance.

The regulation falls under the jurisdiction of Cfius, an interagency committee with the authority to review transactions that may result in foreign persons or businesses controlling certain types of business in the US, to ascertain their impact on US national security.

Chinese investment volume patterns

Source: Baker McKenzie

On January 13, the US Treasury Department issued two sets of final regulations under FIRRMA. The first related to Cfius' expanded jurisdiction over certain types of investments, including non-controlling investments in certain US businesses, while the second related to its expanded jurisdiction over certain foreign investments in real estate.

The link between the tariff escalation and Cfius' new powers might not be direct – but it exists. "While Cfius is not directly related to the trade war, it is in the minds of directors and sellers. There is the general preoccupation with both," says Randy Cook, senior managing director at consulting firm Ankura. "Because of this discussion of tension – even though it doesn't really relate to investment – people are panicky to do things at a psychological level."

Not all parties agree that Cfius has a major impact on the trade war though. "It's tempting to focus on the impact of the new Cfius regulations on the US-China relationship, not least because when the law underlying these regulations was passed in 2018, members of Congress and the administration emphasised the potential threat to national security posed by Chinese investment in the US," says Jeremy Zucker, partner at Dechert in Washington DC.

|

|||

|

Either way, US companies and foreign investors from around the globe – not just China – should recognise the impact these new regulations will have. Cfius' jurisdiction over foreign investment transactions has expanded in a meaningful way to cover new types of investments, and filings are now mandatory for certain transactions.

"Chinese buyers have been particularly sensitive about Cfius approval – in fact practically anything to do with the US – for the last few years anyway. They have to ask the question: 'is it likely to trigger Cfius?'," says UBS' Lo.

Putting aside the spillovers from the trade frictions between China and the US – which will not go away anytime soon – changes to the policy environment governing Chinese investments into the US are conditioned by the enactment of FIRRMA and its implementing regulations. However there are other factors – more mundane perhaps, but critical – that need to be considered carefully when assessing cause and effect.

It's also worth noting that the most obvious gauge of sentiment – FDI levels – do not tell the full story. "I'm always wary of most analysts' view of China's FDI statistics for two reasons. First, they are largely based on signed commitments made by the Chinese side to invest; rarely do they measure actual consummation of investments on the ground," says Berkeley Research Group's Broadman. "Inflows and outflows of FDI are indicative, but I am not sure they provide any hard and fast conclusion that is economically meaningful."

Either way, there's little question that Chinese investors have been put off by both FIRRMA and the current administration's Cfius approach. In meetings with Chinese investors and US firms looking to attract more capital from China, as well as US law firms advising such businesses, Broadman has heard a palpable, consistent refrain from the Chinese side that the US is closed. "This perception is, to some extent, misplaced," he says. "It's typically based on the false assumption that the only US sectors worth investing in are the so-called pilot industries specified under the Cfius regulations."

By and large, though, Chinese firms are not pursuing US deals – even in non-contentious areas. This could be because guidelines on when a Cfius notification is triggered are quite vague. That decision is largely subject to the administration's feeling on the specific deal – which doesn't scream predictability.

Even minority stakes are now up for review now too, which was not the case previously. "Dealmakers just don't know how to interpret it. In the absence of better information or precedent, they think it makes more sense to just stop completely," says Lo.

"A lawyer's immediate reaction – in some cases before they've looked at the particulars – is that of course it will trigger a Cfius review. Then comes the recommendation for a full team of Washington lawyers," he says.

It's worth noting that national security concerns about Chinese investment are not unique to the US. For decades now there's been a steady flow of capital from the country into practically every region; the high watermark probably being the ChemChina acquisition of Syngenta in 2017. "Since then, if there have been deals, players have been quite proactive about security and regulatory concerns," the head of M&A at a major global bank tells IFLR.