Mohamed Nabil Hazzaa, Ibrahim Shehata and Basma Seif of Sharkawy & Sarhan Law Firm look at how Egypt has revamped its procurement laws to boost private participation in infrastructure projects

Egypt is the most populated country in the Middle East and the third most populous in Africa. Over 100 million inhabitants are concentrated in only 6.8% of the country's one million square kilometres. In accordance with its 2030 vision, the Egyptian government is currently taking important steps to spread the country's population to newly established satellite cities including New Cairo, New Giza, New Mansoura, New Sohag, New Alamein, New Borg Al Arab and New Minia.

Transportation, water and electricity are all crucial to the existence and sustainability of new satellite cities. Further, being part of the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that seeks to interconnect and boost global trade requires upgrading the current infrastructure in order to harvest the benefits of such an aspiring plan. It is estimated that approximately $230 billion of investment is required to meet Egypt's infrastructure needs over the next 20 years. The Egyptian government is focused on turning to the private sector for active participation and partnership in order to achieve its infrastructure goals. With the backing of unprecedented political will, the infrastructure space in Egypt offers significant opportunities for both local and international players.

There are three main legal schemes for procuring infrastructure projects in Egypt: The Public Procurement Law of 2018 (Law 182); The Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Law; and the Sector-Specific Law. The Egyptian government has great leeway in choosing between them when tendering infrastructure projects.

The legal framework

Public procurement law scheme

The most standard legal framework for public infrastructure projects is Law 182. It was issued at the end of last year and replaced the Tenders and Bids Law no. 89 of 1998 (Law 89). Law 182 was enacted to improve efficiencies and provide value for money to the government, whilst fighting corruption and institutionalising the principles of transparency, fairness and equal opportunity. Law 182 has a wide scope as it regulates the conclusion of contracts tendered by most public bodies. For instance, it applies to contracts concluded by ministries, as well as, most governmental agencies.

Among its special features are direct agreements. Tendering by direct agreement allows the governmental entity to enter into contractual arrangements without following the traditional and lengthy tender procedures prescribed under Law 182. Tendering by direct agreement has clear advantages for the bidders. For example, it allows bidders to enter into discussion with the government or relevant ministry at an early stage to work together for the benefit of a successful outcome. This tender process is potentially both more efficient for and cost effective to the private sector.

Although tendering by direct agreement was available under Law 89, it was limited to cases of urgency and necessity. This concept was rather ambiguous and difficult to define, especially before Egyptian Courts. Law 182 currently provides a rigorous definition of when direct agreements can be used, along with the financial cap for each specific type of transaction. This is one of the reasons why we anticipate that tendering by direct agreement will be used more often by the government in the upcoming period.

According to Law 182, the Cabinet of Ministers can also allow a governmental authority to enter into a direct agreement with either an international or an Egyptian entity initiated through an unsolicited bid by the private sector entity. Any such bid has to include a comprehensive project proposal and a proposed financing package. Further, any such project must achieve the economic and development goals of the government.

Another special feature is that Law 182 enables governmental authorities to enter into complex transactions such as BOOT, BOO, and EPC+Finance without being bound to follow the conventional tendering methods under Law 182. This is conditional upon such projects being essential to the relevant governmental authority in order that it may: achieve its imminent economic and development goals; or that economic and social circumstances require the prompt conclusion of such contracts within a specific time frame. A special ministerial committee will further extrapolate the procedures and conditions for such an exception in the form of a procedural guide to be approved by the Cabinet of Ministers.

According to Law 182, all tenders, including those procured by direct agreement, must be published online on the Public Procurement Portal, except for transactions that have national security implications. The publication must include the procurement method, its conditions and reasons for following that particular tender process, the technical and financial evaluation methods, and any other data specified by the executive regulations of Law 182 (yet to be issued).

PPP scheme

The PPP Law was enacted by the Egyptian government in 2010 to encourage the private sector to actively participate in developing infrastructure projects and to ease the financial burden on the public budget. It governs contracts concluded between the public and private sector for infrastructure projects and public services and utilities. The contract term can be for more than 30 years, if the approval of the Cabinet of Ministers is obtained.

The structure of the Egyptian PPP model is mainly based on the UK PPP model. In order to ensure that PPP contracts are properly implemented, the Egyptian government has established two governmental entities that set the framework for PPP projects and supervise their implementation throughout their term (see Table 1).

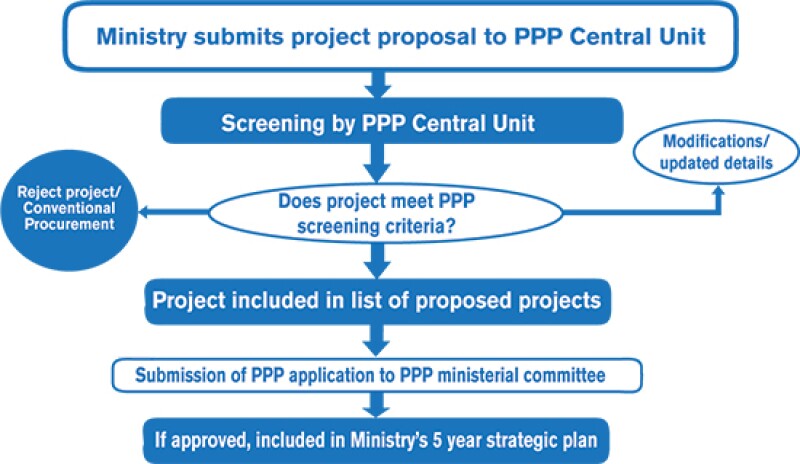

The role of the PPP Central Unit starts from project screening, tendering and procurement, and bid selection to post award monitoring. It works with the relevant ministries closely to implement PPP projects. During the screening and approval project phase, the PPP Central Unit provides technical assistance to select bankable projects that meet the needs of the public sector (see Table 2).

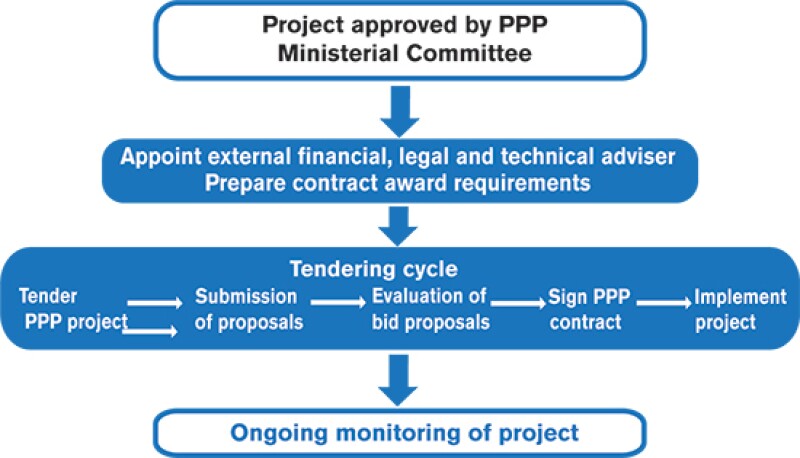

Once a PPP project is approved by the ministerial committee, it goes to the tendering and monitoring project cycle. The PPP Central Unit at this stage assists the awarding governmental authorities in the selection of service providers and ensures public sector contributions to the PPP project are optimised and monitored throughout the life of such project (see Table 3).

Currently, the PPP law does not allow for the tendering of projects through direct agreements. However, according to several sources, the PPP law will be amended soon to provide for direct agreements and also provide for the possibility of submitting unsolicited bids by the private sector. These prospective amendments evidence the Egyptian government's continued commitment to aligning with international best practices, through its review and reform of key laws designed to attract investment. This demonstrates increased efficiency and accountability on the part of the Egyptian government in matters of public spending.

Table 1

Government entity |

Mission |

Supreme Committee for PPP Affairs |

• Chaired by the Prime Minister, with the membership of several ministers and the head of the PPP Central Unit; • Sets an integrated national policy for PPP; • Identifies the framework for PPP projects; and • Concludes studies aiming at developing market tools necessary to provide appropriate financial structure for PPP projects. |

PPP Central Unit |

• Established within the Ministry of Finance; • Provides technical, financial and legal advice to the Supreme Committee for PPP Affairs; and • Aligns with the relevant governmental authorities to implement the awarded PPP projects. |

Table 2

Table 3

Sector-Specific Law scheme

This scheme grants a governmental authority in a specific sector an additional method for tendering and procuring projects within its sector. The Sector-Specific Law scheme is currently not available for all infrastructure projects. It is, however, available for railway projects, metro lines, ports and the electricity sector.

Procuring a project under this scheme is subject to the approval of the Cabinet of Ministers. Following such approval, the tendering and procurement process must be carried out in a transparent and public manner. Additionally, each sector sets the main conditions and available tenors for projects to be procured using this scheme. Under Section (3) of this article, special attention is given to examples of the Sector-Specific Law scheme in the transportation sector.

Focus on Promising Sectors

Water projects

Water and sanitation are key challenges for Egypt, as the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam along with a rapidly expanding population are resulting in an annual water deficiency of 54 billion cubic meters. This has in turn spurred fears of water scarcity in Egypt. These fears are the driving forces behind the government pledging $51 billion for water projects over the next 20 years. Egypt could fill this massive gap with desalinated seawater, the reuse of drainage water, shallow ground water and treated wastewater.

The schemes currently available for procuring water infrastructure projects are the Public Procurement Law and the PPP Law. Historically, the PPP Law was used for procuring projects in this sector. Since the enactment of Law 182 with its special features (ie, Complex Projects Procurement), it is unclear which procurement process the government will choose for this sector going forward.

It is anticipated that a new law will be issued to regulate the water sector, including wastewater treatment and water desalination projects. It is expected that the new law will provide an all-inclusive framework that will incentivise the private sector to invest in water infrastructure projects and will deal with sector specific issues in a more pragmatic and investor friendly way. Until the issuance of such law, we envisage that the imminent infrastructure projects in the water sector will continue to be tendered under the umbrella of the PPP Law.

Furthermore, new trends have been emerging in the sector. In the beginning of 2018, a new project was completed in Borg El-Arab, Alexandria, whereby solar energy was used to power up a water desalination facility. This multi-faceted facility produces 1 MW of electricity from solar energy, and 250 cubic meters per day of desalinated water. This could signal a new industry trend whereby Egypt banks on its abundant solar energy resources to build cost-efficient water desalination facilities.

There are also plenty of project opportunities across various sectors. With 19 new water desalination plants currently under construction and an additional 16 plants to be tendered soon, Egypt will almost quadruple its desalinated water production by 2022. Expanding and upgrading mega-urban wastewater treatment facilities also remains a top government priority. According to several sources, extensive discussions are being held with several international and local investors. It seems that this would be a good time for interested parties to approach the Egyptian government in order to begin discussions and exchange ideas on concerns and solutions.

Transport infrastructure

Transport infrastructure is a current priority area for development as the Egyptian government is looking to roll out several mega-projects in this sector. The process of refurbishing ports and railways is under way, but in need of further investment, and private sector partners are needed. According to a World Bank analysis, Egypt faces a projected gap in transportation infrastructure of $180 billion over the next 20 years.

The Egyptian authorities have recently initiated several legislative amendments with the aim of making investments in railway and metro projects attractive to private investors. These amendments grant the Egyptian authorities unprecedented flexibility in negotiating and selecting the private investors who will help revamp transportation infrastructure.

The changes introduce a concession-based project for a maximum of 15 years, allowing the relevant authorities to seek direct participation by private investors in developing the railway and the metro systems. We understand that the Ministry of Transportation appreciates the bankability challenges that a 15-year concession term represents and that a solution is being actively sought.

These amendments do not necessarily mean that this is the only way to procure railway and metro projects in Egypt. It is still possible to do so using one of the two other schemes (i.e., Law 182 and PPP Law). The amendments simply provide an additional route to the government to procure public infrastructure projects in the transportation sector.

There are again plenty of opportunities in the transport sector. A high speed electric train project (passengers and cargo) that will connect the Red Sea port of Sokhna to the Mediterranean Sea port of Alexandria (300 km) is anticipated. The tender is likely to be offered on an EPC+Finance basis. This project has already attracted great interest from a number of consortia including companies from Europe and China, in particular. Egypt has recently issued a tender for two monorail projects; one to link 6 October City to Giza (35 km) and the other to link the New Administrative Capital to Eastern parts of Cairo and Downtown (52 km). Tender documents on an EPC+Finance basis have been issued and selection is expected soon. This tender is also attracting interest from European and Chinese companies.

The Egyptian government has also announced future projects for six metro lines and five interactive stations while developing the existing transportation services of the first and second lines by 2050. It is expected that these projects will increase the number of daily commuters to 9 million.

Keeping the momentum

The Egyptian government has shown both the commitment and the ability to be effective when it comes to upgrading its infrastructure. In 2010, Egypt was suffering from crippling electricity shortages. Less than a decade later in 2019, the government is looking to export electricity to neighbouring countries. During this period, the government has successfully increased its electricity output, upgraded its electricity infrastructure and introduced clean energy to its energy mix; all through capitalising on its renewable energy resources such as solar and wind energy. In the process, the government has attracted ample foreign and local investments through its extremely successful feed-in tariff program. Recently, the World Bank has applauded the government's efforts by declaring the Benban Solar Park its top project of 2018. This is a true testament to the government's willingness to do all it can to unlock the economy's full potential and achieve its 2030 vision for Egypt.

In addition, the legal schemes for procuring mega-infrastructure projects in Egypt have been reformed to a large extent so as to facilitate the procurement process for all parties. It can be stated with confidence that Egypt has developed a cutting-edge legal and regulatory framework that can foster foreign direct investment. Further, the government enjoys great flexibility and can, in principle, choose the most fitting scheme on a case by case basis for implementing mega-infrastructure projects in Egypt (ie, Public Procurement Law scheme, PPP Law scheme, or Sector-Specific Law scheme).

The government is looking to replicate its success story in the electricity sector in the infrastructure sector; specifically, the water and transportation sectors. Investors should be encouraged that the government has the necessary legal tools and the political determination to successfully proceed with these ambitious and prosperous plans.

About the author |

||

|

|

Mohamed Nabil Hazzaa Partner, Sharkawy & Sarhan Cairo, Egypt T: +202 23 22 54 00 Mohamed Nabil Hazzaa is a partner at Sharkawy & Sarhan Law Firm with 10 years of experience in corporate and commercial law. He has unparalleled experience of advising on transactions in the energy, infrastructure and banking sectors. Mohamed is a leading lawyer in the budding renewable and alternative energy industry in Egypt. His experience covers solar, wind and alternative fuels technologies. Most notably, he advised seventeen international financial institutions including the EBRD, IFC, Proparco, CDC, AfDB, AIIB on the financing of the 1.8 GW Benban Solar Park under rounds I and II of the Egyptian Feed-in Tariff Program. The transaction was awarded Thomson Reuters' Global Multilateral Deal of the Year. Mohamed also regularly advises on M&A transactions in various sectors including the banking sector. He recently advised Attijariwafa Bank on its $495 million acquisition of Barclays Bank Egypt. |

About the author |

||

|

|

Basma Seif Senior associate, Sharkawy & Sarhan Cairo, Egypt T: +202 23 22 54 00 Basma Seif is an experienced top tier transactional lawyer and senior associate at Sharkawy & Sarhan Law Firm. Both multilingual and multicultural, Basma specialises in complex finance transactions covering a range of sectors including power, infrastructure, oil & gas and financial technology (fintech). She has also acted on project financing transactions and on major M&A deals in the banking sector. Basma played a leading role in advising seventeen international financial institutions including EBRD, IFC, Proparco, CDC, AfDB, AIIB on the financing of the 1.8 GW Benban Solar Park under rounds I and II of the Egyptian Feed-in Tariff Program. The transaction was awarded Thomson Reuters' Global Multilateral Deal of the Year. Basma continues to build upon the vast experience she gained from her previous work at Clifford Chance (France and Morocco) and at Orrick (France). She holds a masters' degree in business law from the University of Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne (France). |