The 2007–2009 financial crisis has shown the important role of the lender of last resort in restoring financial stability in the financial markets. A rethink of this doctrine is therefore needed. This article shows how a potential lender of last resort regime can be designed for the 21st century.

WHAT IS THE LENDER OF LAST RESORT?

The term lender of last resort (LOLR) is believed to have been used for the first time by Sir Francis Baring in Observations on the Establishment of the Bank of England and on the Paper Circulation of the Country in 1797. Baring used a French legal term for a court of last appeal, dernier ressort, from which banks can obtain emergency liquidity assistance (ELA).1 Baring indicated the Bank of England, at that time a bank, as being the lender of last resort, from which all borrowers, typically banks, could obtain ELA in times of financial distress.2 In this context, the LOLR can be defined as follows:

Definition of the lender of last resort |

The lender of last resort is an institution from which all borrowers, typically banks, can obtain emergency liquidity assistance in a financial distress situation. |

According to this definition, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) acts as the LOLR in Switzerland if the following three conditions are fulfilled3:

'The bank or group of banks seeking credit must be of importance for the stability of the financial system.

The bank seeking credit must be solvent.

The liquidity assistance must be fully covered by sufficient collateral at all times. The SNB determines what collateral is sufficient.

To assess the solvency of a bank or group of banks, the SNB obtains an opinion from FINMA'.

CHALLENGES OF THE LENDER OF LAST RESORT

The 2007–2009 financial crisis has shown the important role of the LOLR in restoring financial stability in the financial markets (in particular in the Union Bank of Switzerland (UBS) crisis). Although the rescue of UBS was successful and reduced unnecessary risk in the banking industry, ELA by the LOLR is subject to various problems. First, ELA creates an uneven playing field between systemically important banks (SIBs) and small and medium-sized banks because SIBs benefit from cheaper funding.4 Second, ELA can lead to moral-hazard because the LOLR creates incentives to take more of the insured risk, that is, the liquidity risk.5 Thus, with ELA, 'investors do not fully price in bank risk-taking and banks are incentivised to take more risk than they would if their cost of funding reflected their activities'.6 Third, ELA creates costs for the public sector because if central banks suffer losses, they will transfer these costs to the governments.7 Consequently, the taxpayer bears a substantial proportion of the losses. Fourth, ELA creates macroeconomic costs; for example, the rescue packages from the Swiss Confederation and SNB covered only 4% of UBS's balance sheet but cost 13% of the GDP in Switzerland (government expenditures for one year).8 Fifth, ELA represents a reputational risk for the banking sector and affects confidence in banks and shareholders.9 These deficiencies led to a rethink of the LOLR doctrine.

RETHINK OF SWITZERLAND'S LENDER OF LAST RESORT REGIME

The experience of the Swiss LOLR during the recent financial crisis raised fundamental questions about the design of the LOLR framework and the execution of a more stable financial system in the twenty-first century. In this context, the challenge will be to design an LOLR regime that financial institutions are prepared to use to contain liquidity and solvency crises and their wider social costs before it is too late.10 A regime such as the LOLR would not work well when market participants believe that the SNB has no clear principles in place. In this connection, we propose that the Swiss LOLR should depend on the following three main conditions:11

The liquidity-seeking bank or group of banks must be of systemic importance to the financial system's stability.

The bank must be solvent or temporarily insolvent.12 This principle differs from the current LOLR condition. In times of financial distress, it is generally impossible to distinguish between illiquidity and insolvency unless the central bank has a good knowledge of the bank. Further, if an illiquid bank requires ELA, a supposition of solvency must exist – otherwise, under normal economic conditions, the bank will receive liquidity against good collateral on the interbank market.13

The liquidity assistance must be fully covered by good collateral at all times on a risk-based premium. The SNB will determine what types of collateral are good. The third Swiss LOLR condition differs in terms of the collaterals and a new component, namely a risk-based premium. Good collateral means that the SNB should lend against collateral against which money can be readily obtained in normal times. We added a risk-based premium because lending at a risk premium could be very profitable.14 However, we are sceptical about lending at a very high interest rate because such a rate could be self-defeating if 'the cost of assistance would exceed the cost of liquidating illiquid assets'.15 Therefore, instead of lending at a very high interest rate, we propose lending at a high interest rate, the so-called 'risk-premium', based on the risk in normal times and a premium (for example, 250 basis points).

In addition to these three principles, we can add inter alia the following nine principles:16

In times of financial distress, the SNB should primarily act as the market maker of last resort (MMLR) and, if required, as the LOLR.

ELA from the LOLR is endogenous and created based on demand. Endogenous means that the LOLR accommodates the demand for ELA due to the nature of money and credit. In other words, if banks demand ELA, the central bank acts as the LOLR and offers ELA, on which the LOLR sets an interest rate according to its creditworthiness.

The LOLR is non-operational (not a discount operation and open market operations (OMOs)) because otherwise inside liquidity and thus the provision of high-powered money via OMOs or discount window transactions would be sufficient.

The Swiss LOLR should be based on a cost-benefit analysis.

To improve monetary policy operations and LOLR operations, the SNB should assess the solvency of SIBs.

The Swiss Confederation should be excluded from liquidity support.

The Swiss LOLR should be based on a broad, explicit, and transparent fiscal carve-out condition. If the central bank suffers losses, they transfer the cost to the government, which must cover the cost through higher taxation or public spending cuts. This transfer of fiscal cost is an implicit fiscal carve-out. Therefore, the LOLR regime requires a broad fiscal carve-out condition.17

The Swiss LOLR requires various memoranda of understanding with different central banks and regulatory authorities.

Fundamentally insolvent financial institutions should be allowed to enter into liquidation/bankruptcy.18

Rethinking of Switzerland’s lender of last resort regime

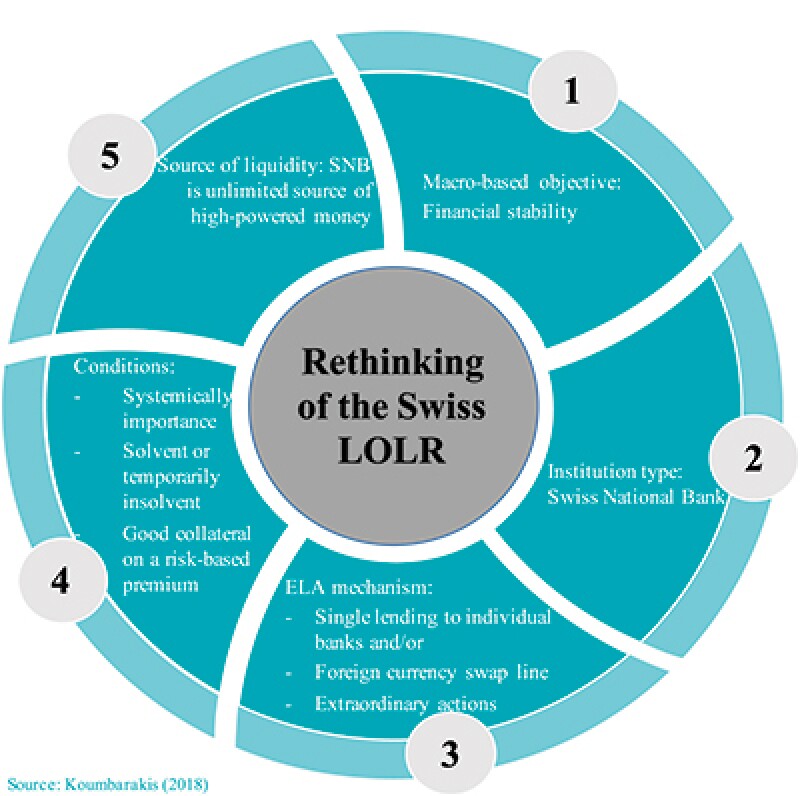

According to these principles, we can rethink the Swiss LOLR using the following scheme, which draws upon five main characteristics: (1) the type of objective; (2) the type of institution; (3) the ELA mechanism; (4) ELA requirements; and (5) the source of liquidity. The diagram shows the potential reform proposal with respect to these five characteristics. The Swiss LOLR's main objective is financial stability. In this context, the SNB is not responsible for preventing the initial failure but for keeping a subsequent wave of failures from spreading through the financial system. The LOLR thereby provides ELA to banks that are systemically important to the Swiss economy.19

In relation to being a limited or ultimate source of liquidity, we would point out that (1) the SNB has had a unique role in terms of the stock of high-powered money (SNB notes) because no other institution has the right to issue SNB notes. Thus, the SNB has a monopoly in the creation and management of domestic high-powered money. Moreover, the SNB can create unlimited foreign high-powered money. To do so, the SNB has to enter into a swap arrangement, as was the case in the financial crisis of 2007-2009 (e.g. swap arrangement with the Federal Reserve Bank). Therefore, the LOLR is practically unlimited source of ELA because of its creation of domestic high-powered money and its swap transaction in foreign high-powered money.20

According to the ELA mechanism, the Swiss LOLR can provide ELA in the following three forms: (1) single bilateral lending via the discount window (2) direct foreign currency swap lines, and (3) extraordinary actions such as asset and liability transformation to an SPV (e.g. Stab Fund).

THREE PRINCIPLES FOR REFORM

The 2007–2009 financial crisis has shown the important role of the LOLR in restoring financial stability in the financial markets. A rethink of the LOLR doctrine is therefore needed. In this context, we propose to reform the Swiss LOLR according to the following three main principles: (1) The liquidity-seeking bank or group of banks must be of systemic importance to the financial system's stability. (2) The bank must be solvent or temporarily insolvent and (3) The liquidity assistance must be fully covered by good collateral at all times on a risk-based premium.

About the author |

||

|

|

Dr. rer.pol. Antonios Koumbarakis Manager, Legal FS Regulatory and Compliance Services PricewaterhouseCoopers Zurich, Switzerland T: +41 58 792 45 23 M: +41 76 406 1207 E: antonios.koumbarakis@ch.pwc.com W: www.pwc.com Antonios Koumbarakis is a Manager within PwC Zurich and a team member of its Legal FS Regulatory & Compliance Services practice. Antonios specialises in regulatory project management, project execution and central bank support in Switzerland, Europe and Middle East. He is a subject matter expert in bank regulation (such as Mifid II, Basel III, Basel IV, TBTF regulation such as securitisation framework, capital requirements, liquidity requirements and recovery and resolution standards) and monetary policy. Antonios holds a master of arts in economics (lic.rer.pol) from University of Fribourg (Switzerland) and he has wrote his PhD thesis in the area of macroeconomics and monetary economics. He was a Visiting Research Fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods in Bonn with a research focus in monetary policy, financial stability and bank regulation. Moreover, he has participated in the London School of Economics’ Executive Education Program. |

About the author |

||

|

|

Dr. iur. Guenther Dobrauz-Saldapenna, MBA Partner, Leader PwC Legal Services Switzerland & Leader PwC Legal FS Regulatory and Compliance Services PricewaterhouseCoopers Zurich, Switzerland T: +41 58 792 14 97 M: +41 79 894 58 73 E: guenther.dobrauz@ch.pwc.com W: www.pwc.com Guenther is a Partner with PwC Zurich and Leader PwC Legal Switzerland as well as Leader of the PwC Legal FS Regulatory and Compliance Services practice. Guenther is also a meber of PwC's Global legal Ledership team. He specializes in supporting the structuring, authorization and ongoing lifecycle management of financial intermediaries and their products. In addition, he is focused on leading and supporting the implementation of large scale regulatory change and compliance alignment projects at Swiss and international financial institutions with particular focus on EU regulations and Swiss regulations. He received his Masters and PhD degrees in law from Johannes Kepler University (Linz, Austria). Guenther also holds an MBA from the University of Strathclyde Graduate School of Business (Glasgow, UK) and has participated in Harvard Business School’s Executive Education Programs. |

See Grossman, R.S. and Rockoff, H. (2015: 58) Fighting the last war: Economists on the lender of last resort, Working Papers, Department of Economics, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 15.

See Thornton (1965 [1939]) An enquiry into the nature and effects of the Paper Credit of Great Britain, New York: Augustus M. Kelley Bookseller.

See Swiss National Bank (SNB) (2018) Guidelines of the Swiss National Bank on monetary policy measures of March 25 2004, Zurich: Swiss National Bank.

See Birchler et. al. (2010) Faktische Staatsgarantie für Grossbanken, Gutachten erstellt im Auftrag der SP Schweiz, Institut für schweizerisches Bankwesen, Universität Zürich.

See Tucker, P. (2014) The lender of last resort and modern central banking: principles and reconstruction, in Bank for International Settlements (ed.) 'Re-thinking the lender of last resort', Bank for International Settlements Papers, No. 79, September, pp. 10-42.

Liikanen et al. (2012: 23) High-level Expert Group on reforming the structure of the EU banking sector, Brussels: European Commission.

See Hellwig, M. (2014) Financial Stability, Monetary policy, Banking Supervision and Central Banking, Preprints of the Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods, No. 9, July.

See Birchler et. al. (2010) Faktische Staatsgarantie für Grossbanken, Gutachten erstellt im Auftrag der SP Schweiz, Institut für schweizerisches Bankwesen, Universität Zürich.

See Baltensperger, E. (1992) Central Bank Policy and Lending of Last Resort, Proceedings of the: Conference on Prudential Regulation, Supervision and Monetary Policy, Università Bocconi-Milano, in Giornale degli Economisti e Annali di Economia, Nuova Serie, Anno 51, 9 (12), pp. 441-452.

See Tucker, P. (2014) The lender of last resort and modern central banking: principles and reconstruction, in Bank for International Settlements (ed.) 'Re-thinking the lender of last resort', Bank for International Settlements Papers, No. 79, September, pp. 10-42.

See Koumbarakis, A. (2018) The Economic Theory of Bank Regulation and the Redesign of Switzerland's Lender of Last Resort Regime for the Twenty-First Century, Schulthess Verlag.

Opponents would criticise lending to temporarily insolvent banks but distinguishing between fundamental insolvency and temporary insolvency is useful. Fundamental insolvency means that a bank is insolvent and unable to return to viability, even in the medium and long run. Temporary insolvency means that in times of distress, the bank can be referred to as insolvent, but it can become viable and thus solvent in the medium and long run. According to this conceptual distinction, the political legitimacy used to justify the central bank's ELA on equity grounds is easier than in the case of fundamental solvency (see Koumbarakis, A (2018) The Economic Theory of Bank Regulation and the Redesign of Switzerland's Lender of Last Resort Regime for the Twenty-First Century, Schulthess Verlag).

See Goodhart (2009 [1999]) 'Myths about the Lender of Last Resort', in Goodhart, C.A.E. and Illing, C. (eds) Financial Crises, Contagion, and the Lender of Last Resort, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 227-245 and Tirole (2002) Financial crises, liquidity, and the international monetary system, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

See Hellwig, M. (2014) Financial Stability, Monetary policy, Banking Supervision and Central Banking, Preprints of the Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods, No. 9, July.

Guttentag and Herring (1987: 166-167) 'Emergency liquidity assistance for international banks', in Portes, R. and Swoboda, A.K. (eds) Threats to International Financial Stability, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 150-194.

A complete systemic analysis of the Swiss LOLR can be found in Koumbarakis, A (2018) The Economic Theory of Bank Regulation and the Redesign of Switzerland's Lender of Last Resort Regime for the Twenty-First Century, Schulthess Verlag.

See Hellwig, M. (2014) Financial Stability, Monetary policy, Banking Supervision and Central Banking, Preprints of the Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods, No. 9, July.

See Tucker, P. (2014) The lender of last resort and modern central banking: principles and reconstruction, in Bank for International Settlements (ed.) 'Re-thinking the lender of last resort', Bank for International Settlements Papers, No. 79, September, pp. 10-42.

The SNB should also rethink their role for systemically important non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) that can have an impact on the Swiss economy because what would happen if a systemically important NBFI (such as Zürich Insurance or SwissRe) failed (see Koumbarakis, A. (2018) The Economic Theory of Bank Regulation and the Redesign of Switzerland's Lender of Last Resort Regime for the Twenty-First Century, Schulthess Verlag).

Goodhart (2009 [1999]) noted that the domestic LOLR is a limited source of liquidity. A domestic LOLR has limited liquidity because it cannot create foreign currency and it has limited capital, as the strength and taxing power of the government is behind the liabilities rather than the capital of the central bank.