The country’s fiduciary regime offers an efficient solution for funds looking to tap the region’s loan market

With banks required to reduce their asset base by trillions of dollars over the next few years, alternative lenders such as debt funds are increasingly filling the gaps left by these traditional lenders. One of the key aims of the European Commission, in its green paper and action plan on the building of a Capital Markets Union, is to 'enable alternative means of financing to develop'; in other words, to provide more funding choices for Europe's businesses and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). In its action plan, the Commission acknowledges the existence of these alternative lenders as large institutional investors or investment funds that invest in or directly originate loans to mid-sized firms and indicates that they could emerge as a potentially important future source of non-bank credit.

However, these alternative lenders, in particular loan origination funds, often face national barriers – such as banking monopoly restrictions – for direct lending to corporates in a number of countries throughout Europe. Unregulated, and even regulated, funds are often deprived of direct access to such markets on the grounds of such local bank monopoly rules. A potential way out of this cul-de-sac for these alternative lenders consists of setting up specific (licensed) lending vehicles in the relevant jurisdictions or confining their lending activity to specific types of borrowers or the acquisition of existing loans, rather than so-called proper loan origination. Removing these entry barriers to enable cross-border investment for pan-European loan origination vehicles is, therefore, key.

One solution may be found in the use of the Luxembourg fiduciary regime (the Luxembourg Act, July 27 2003 relating to trust and fiduciary contracts, as amended (the Trust and Fiduciary Contracts Act 2003)) as a tool for direct lending for debt funds. Here's how it works.

The proposed structure

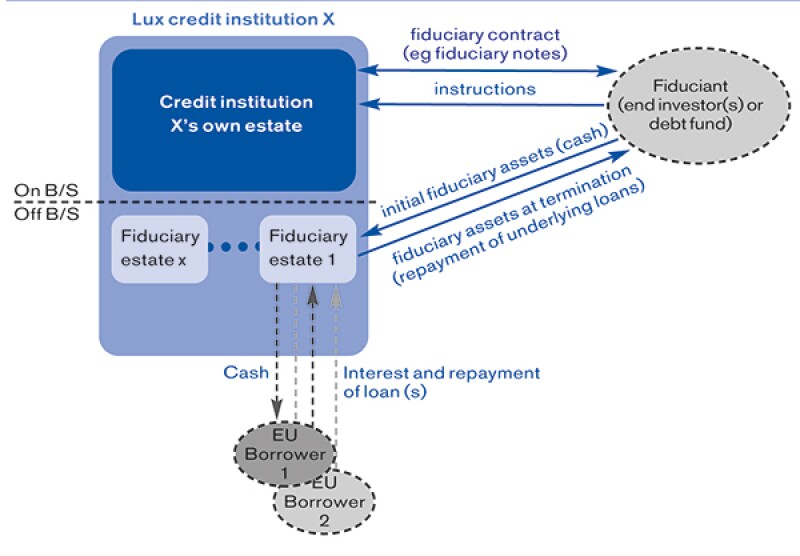

Under the proposed structure, a credit institution – in principle a Luxembourg credit institution – serves as fiduciary in accordance with the Trust and Fiduciary Contracts Act 2003. Pursuant to the Act, the fiduciary can, upon instruction from one or more investors (the fiduciants) under a fiduciary contract, create a segregated fiduciary estate, which is held off balance sheet of the Luxembourg credit institution. In the proposed structure, the fiduciary estate is funded either by an intermediary debt fund or directly by end investors (via fiduciary notes, as further discussed below). The monies held in the fiduciary estate are then used to grant loans to the relevant borrowers in the relevant EU jurisdictions on the basis of the bank's EU passport for banking services.

A fiduciary can create any number of separate, ring-fenced fiduciary estates. A fiduciary estate can either grant a single loan or have a portfolio of loans. Potential borrowers could be both legal and physical persons located in any EEA jurisdiction. The loans may be collateralised by specified assets.

The legal framework

By way of general background, according to the Trust and Fiduciary Contracts Act 2003, a fiduciary contract is an agreement between a fiduciary (fiduciaire) and a principal/fiduciant (fiduciant). Here, the fiduciant confers ownership rights over specific assets (the fiduciary assets) to a fiduciary, subject to the obligations set out in the fiduciary contract. The fiduciary obtains legal title over the assets designated in the fiduciary contract. Upon the termination of the agreement, the fiduciary assets are transferred back to the fiduciant (or to a third party beneficiary). In the proposed structure, the fiduciant transfers cash to the fiduciary, which will, upon receipt, be used to grant loans in accordance with the instructions of the fiduciant set out in the fiduciary contract. Only specified entities may, under the Trust and Fiduciary Contracts Act 2003, act as a fiduciary. In practice, it is mainly Luxembourg credit institutions that are active in this business.

|

|

"The only real obstacle may lie with the fact that these structures are, for the time being, perceived as atypical" |

|

|

The fiduciary assets entrusted to the fiduciary are, as mentioned above, held by the fiduciary in segregated fiduciary estates, which are recorded off balance sheet by the fiduciary and do not form part of the fiduciary's own estate. Pursuant to the Trust and Fiduciary Contracts Act 2003, the fiduciary estates are not affected by insolvency proceedings opened in respect of the fiduciary – the personal creditors of the fiduciary cannot seize fiduciary assets for the satisfaction of their claims against the fiduciary.

Fiduciary contracts can be structured in multiple ways, including via fiduciary note issuances, which are used by a whole range of market participants. The fiduciary contract then takes the form of a transferable security (a note or certificate) issued by the fiduciary to the fiduciant (ie the investor). The fiduciary invests the proceeds received from the holder into the underlying assets specified in the terms and conditions of the fiduciary notes. These securities can potentially be listed on a market.

A fiduciary for pan-European loan origination

In the proposed structure, a Luxembourg credit institution (duly licenced as a credit institution and having passported relevant banking services in all relevant European Economic Area (EEA) member states) would, in principle, serve as the fiduciary.

The key aspect for the proposed loan origination structure is that the acquisition of existing loans or the granting by the credit institution (acting as fiduciary) of new loans to borrowers throughout the EEA should not give rise to concerns from a banking regulatory perspective; the loan origination would, in principle, be covered by the credit institution's licence as a credit institution.

As a matter of principle, under the EU passport, EEA credit institutions may engage in lending activities in any EEA state without restrictions once the EEA credit institution has notified the competent authority in its home member state (where applicable, under the Single Supervisory Mechanism, the European Central Bank will be involved here) of the banking activities its envisages performing in one or more EEA states – subject to such activities being contained in the list of passportable banking activities.

In order for such structure to work, the fiduciary (a duly licenced Luxembourg credit institution) will of course need to have passported its banking services into all relevant EEA member states, or at least in those member states which are being targeted for investment.

As mentioned above, the setting up of fiduciary estates does not imply the creation of a new legal person that would be separate from the bank itself. Effectively, the legal person granting the loans in respect of the fiduciary estates is the credit institution, acting in its capacity as fiduciary (which will also be made clear in the documentation signed with the relevant borrowers).

The fact that the credit institution is acting for the account of a specific fiduciary estate should not influence the conclusion that the credit institution is authorised to grant loans and/or acquire existing loans in the jurisdictions in which its banking services have been passported. The results of a preliminary analysis based on advice sought in the key European jurisdictions (including the UK, France, Germany, Spain and Italy) are encouraging in that they seem to confirm this point. Of course, it cannot be excluded that there may be certain administrative constraints or questions raised by the relevant local authorities when such structures are rolled out for the first time. The key message to respond with to such queries is that this is merely an application of EU legislation and, in particular, the principle of freedom to provide services within the EEA.

It follows that Luxembourg fiduciary structures could, as a matter of principle, be used for pan-European loan origination without facing particular banking regulatory restrictions – which as mentioned initially appears to be an issue for a number of vehicles engaging in direct lending on a pan-European basis.

Luxembourg’s fiduciary regime |

|

The Luxembourg role

In this type of transaction, the role of the Luxembourg credit institution would typically be confined to the fiduciary role – the bank would typically not intervene in respect of other aspects of the overall transaction (such as management of the portfolio of loans, servicing and enforcement) – these would typically be handled by other parties to the transaction. From the fiduciary's perspective, this limited or passive role is also important given that the fiduciary would generally want to have its role confined to that of a conduit, ie becoming the owner of assets and holding them in accordance with the instructions received from the fiduciant – and avoid any extra liability deriving from other roles.

Using a Luxembourg credit institution as a fiduciary for this type of structure also means that the debt fund or investor does not need to set up its own credit institution for the pan-European loan origination. Given that the relevant credit institution is, effectively, not financially exposed to the fiduciary estates and the activities carried out – the fiduciary estates being segregated from the credit institution's estate – a number of Luxembourg credit institutions have, in the past, made their fiduciary capabilities available to third party players (in return for a fee for the fiduciary services). The required minimum set-up for a debt fund intending to make use of the fiduciary for loan origination is, therefore, quite light.

Financing fiduciary estates

As we have seen, a fiduciary contract can take various forms and can be structured via the issuance of fiduciary notes or fiduciary certificates.

The simplest structure would consist of issuing instruments from the fiduciary estate directly to investors. A fiduciary note or certificate, which is akin to a debt instrument, is issued to the end investors. The fiduciary estate then operates as a debt fund. Fiduciary notes can be admitted to trading on a market, meaning that investors requiring a listed instrument could also potentially invest.

When choosing the appropriate vehicle or instrument in which investors are to invest, multiple aspects – often investor-driven – may, however, need to be taken into account. This may lead to a slightly more complex set-up: a debt fund – established either as an investment fund or a bespoke issuance vehicle (such as a securitisation vehicle) – could here serve for the issuance of financing instruments to investors (for instance, units of a fund, debt instruments issued by the securitisation vehicle). The issue proceeds from the instruments issued by the fund or vehicle are channelled to the fiduciary estates (via a fiduciary deposit for instance, or via the subscription to a fiduciary note issued by the fiduciary to the fund or vehicle), which in turn will use them to grant loans or acquire existing loans. The investment fund or bespoke issuance vehicle can be a regulated one or remain unregulated.

Other considerations

As mentioned, when determining the overall structure that fulfils the needs of the targeted investors, a whole range of tax and regulatory aspects will be of relevance. The intention here is not to describe all possible solutions, or indeed all tax and regulatory aspects, but rather to highlight a few issues that may need to be taken into account when making use of the fiduciary structure in connection with a debt fund, in addition to the banking regulatory aspects of such a structure.

|

|

"A fiduciary can create any number of separate, ring-fenced fiduciary estates" |

|

|

From a regulatory point of view, one point to clarify is whether such a fiduciary structure, especially in the form of a fiduciary note issued to investors, could become subject to particular regulatory constraints in connection with the marketing of such instruments to investors, on top of the EU Prospectus Directive requirements. More specifically, it must be determined whether a fiduciary note issued to investors, and potentially to the public, could be re-qualified, for example as the marketing of an alternative investment fund (AIF) under the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD).

As far as the Luxembourg analysis is concerned, a number of strong arguments suggest the issuance of fiduciary notes should not fall within the scope of the Luxembourg act of July 12 2013 relating to alternative investment fund managers, which implemented the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD) into Luxembourg law. These are, among other things, based on the legal nature of the rights the fiduciant has against the fiduciary (a debt claim). Other jurisdictions in which a fiduciary note is being marketed may, however, not have the same interpretation of the relevant provisions of the AIFMD, and a re-characterisation risk cannot be excluded. The use of a debt fund in the form of an investment fund or a securitisation vehicle on top of the fiduciary platform could potentially help in such situations.

The use of fiduciary estates in the context of debt funds also needs to be analysed from a tax perspective. Questions to be raised include whether a fiduciary arrangement should be considered as tax transparent or not. From a Luxembourg tax perspective (paragraph 11 of the tax adaptation law (Steueranpassungsgesetz)) the arrangement is considered tax transparent: assets held by the fiduciary for the benefit of the fiduciant are attributable to the fiduciant for Luxembourg direct tax purposes.

So from a tax point of view, the principal or investor will be considered to hold the fiduciary assets and to be the beneficiary of the income derived from these assets for the purposes of Luxembourg wealth tax, income tax and municipal business tax. In addition to the Luxembourg analysis, one also needs to assess the tax treatment in the jurisdiction in which the underlying borrowers are located. Here, the preliminary responses obtained from local counsel confirmed the tax transparency for a number of key European jurisdictions, however, the situation was less clear for some jurisdictions and a case-by-case analysis is required.

Another aspect to consider is whether there may be potential withholding tax issues (at borrower level) when using a fiduciary platform for the loan origination.

There is clearly potential for this type of alternative structure for pan-European loan origination. The only real obstacle may, therefore, lie with the fact that these structures are, for the time being, perceived as atypical and not market practice – the main players in the alternative financing space often want to rely on existing, well-proven structures.

By Paul Péporté, counsel at Allen & Overy in Luxembourg