1 Minute read |

Against the backdrop of human tragedy brought about by the Covid-19 pandemic, companies are facing their own battle for survival. Over the past few months, tens of millions of people have been furloughed, made redundant or are working under radically altered circumstances, with the resultant dramatic impact on company revenues and, indeed, business viability. In this follow-on piece to our June 2020 article Equity capital raising during Covid-19: practical tips and as governments and central banks run out of fiscal stimulus options – Baker McKenzie lawyers consider what debt capital markets can offer companies struggling to prevent their liquidity problems from becoming solvency problems. |

In our March 9 article, we considered the immediate impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on capital markets, including contractual implications for securities offerings, ongoing disclosure requirements, practical effects, and the approach of stock exchanges and regulators around the world. That article, published ahead even of the nadir of the current liquidity crisis, focused on resilience: what market participants should be concentrating on to survive the initial impact of the Covid-19 tsunami.

In the ensuing weeks and months, as the world has alternately quivered and rallied in the limbo of lockdown, liquidity in the global debt markets has at times been severely impaired. We have seen rapid and acute widening of bid-offer spreads, a measure of underlying market volatility, and an apparent shrinkage of dealer capacity. On April 14, the IMF warned that Covid-19 would produce "the worst recession since the Great Depression".

It predicted a three percent decline in GDP for 2020 (revised to 4.9% in its World Economic Outlook Update, released June 24) and a cumulative loss to global GDP over 2020 and 2021 of around $9 trillion (revised to $12 trillion in the June update), greater than the economies of Japan and Germany combined. Reflecting the growing economic impact of the virus, World Bank data released on June 8 deepened these gloomy predictions still further, with its baseline forecast envisioning an even worse contraction – 5.2% – in global GDP in 2020, with "per capita income contracting in the largest fraction of countries globally since 1870".

Though policymakers are providing unprecedented support, with sovereign debt already set to spike from hefty stimulus packages, governments and central banks are stretched to their limits. Interest rates in the US, the EU, the UK and Japan began the crisis near zero. Though negative interest rates or interest rate cuts remain an option, central banks continue to perceive quantitative easing through asset purchases to be the more effective and efficient tool to place downward pressure on longer-term rates, to stimulate economic activity and provide support for households, firms and essential services. This policy has been a cornerstone of the US Federal Reserve's Covid-19 response, for instance, which has seen hundreds of billions of newly-created currency used to buy assets.

Against this backdrop, with parts of the world now cautiously lifting lockdown measures – even as others remain locked down trying to contain the virus – we look ahead and consider how the debt capital markets might offer businesses a means through which to repair their balance sheets and aid the recovery.

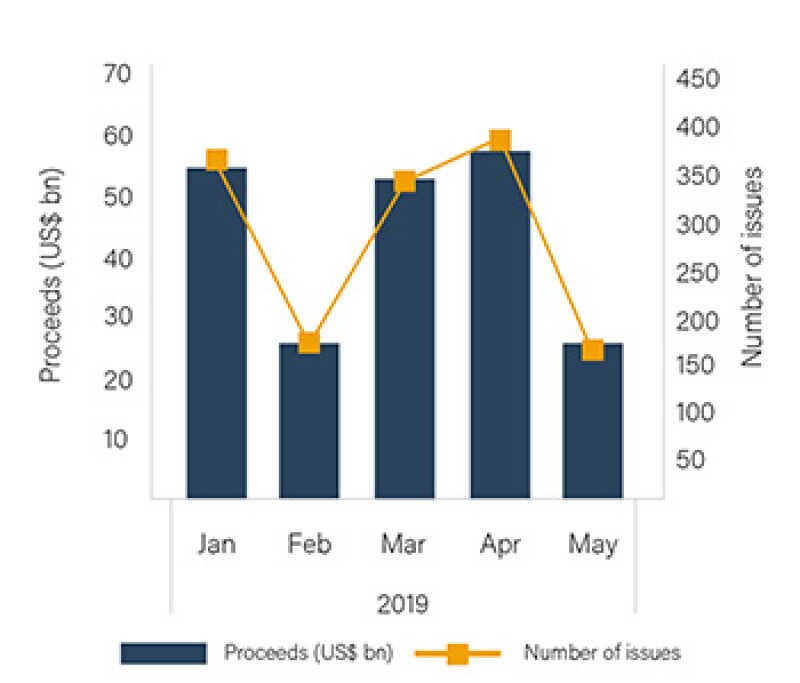

Q1-2 2019 Commercial Paper Issuances

Source: Refinitiv

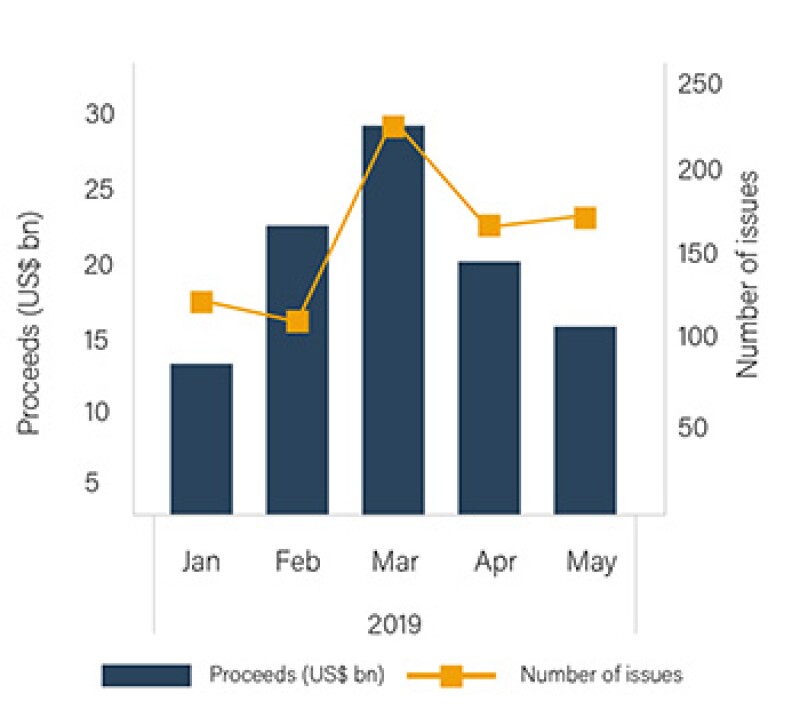

Q1-2 2020 Commercial Paper Issuances

Source: Refinitiv

Quick relief using commercial paper

Recognising the need for urgent cash injections to prevent liquidity problems caused by Covid-19 quickly becoming solvency problems for many businesses, central banks around the world acted swiftly to support the liquidity and financial condition of their local economies, implementing substantial asset purchase programmes to provide near-instant relief for those that qualified.

The ECB's PEPP intervention

On March 18 the European Central Bank (ECB) announced the €750 million ($841.2 million) Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP), under which purchases would be conducted from 26 March. The announcement was key in bringing stability and confidence back to the European secondary corporate bond market.

In addition to covering certain public sector bonds, asset-backed securities and covered bonds, the PEPP expanded the range of eligible assets under the Corporate Sector Purchase Programme (CSPP); a programme through which the ECB buys corporate bonds of eligible issuers on the secondary market. Most notably for eurozone corporate issuers, the scope of the CSPP was expanded to include eligible non-financial commercial paper (CP) with a remaining maturity of at least 28 days (previously a minimum of six months to maturity being required), thereby giving more issuers access to the programmes. The expansion serves several purposes: it helps companies to manage their short-term funding needs, by supporting the provision of greater liquidity through capital markets and thus providing additional incentives for companies to access capital markets.

|

|

Several major stock exchanges have now agreed to waive listing fees for social and sustainable debt instruments that are issued to address Covid-19 |

|

|

In order to be eligible, the CP must fulfil the CSPP eligibility requirements, including (a) as to currency: the CP must be denominated in euro, and (b) credit rating: the first-best rating must have a minimum credit assessment of credit quality step 3 under the Eurosystem credit assessment framework, corresponding to an external credit assessment institution rating of BBB-/Baa3/BBBL.

The equivalent short-term ratings are A-2/P-2/F2/R2-L. The CP must also be issued by a CSPP-eligible entity (i.e. a non-bank corporation established in the euro area) and have either (i) an initial maturity of 365/366 days or less and a minimum remaining maturity of 28 days at the time of purchase, or (ii) an initial maturity of 367 days or more, a minimum remaining maturity of six months, and a maximum remaining maturity of less than 31 years at the time of purchase.

New issuances had all but dried up in the first half of March, yet the PEPP brought the market back from the brink. This resulted in a flood of issues that made March a record month for 2020, with $88.9 billion raised from 610 issues, an increase in proceeds of over 60% compared to March 2019, when $54.1 billion was raised from 341 issues. This flood continued through April, seeing a further $110.2 billion raised from 666 issues, and into May, which saw year-on-year issuances more than double to $55.8 billion.

In the first two months of operation, to end of May, the ECB reported that €35.4 billion of CP had been purchased under the PEPP. Even more strikingly, CP purchases amounted to 76% of the €46 billion private sector debt bought by the ECB during the period, and within that, some 81% – a total of €28.7 billion – was primary issuance.

With total Eurosystem holdings of all securities purchased under the PEPP (including public sector securities, corporate bonds and covered bonds) already reaching €234.7 billion by the end of May, the ECB recognised that the initial €750 billion envelope set aside for the PEPP to the end of 2020 would likely be insufficient. On June 4 the ECB exceeded the market's expectation with the announcement that it would be injecting a further €600 billion into the PEPP, taking its overall investment in the programme to €1.35 trillion and extending the horizon for net purchases under the PEPP to at least the end of June 2021.

The Bank of England's Covid-19 Corporate Finance Facility

Similar in intent to the PEPP extension of the CSPP in Europe, on March 23 the Bank of England (BoE) made a CP purchase programme available to non-financial UK-incorporated companies, ostensibly to help them to pay short-term liabilities, such as wages and suppliers, while they are suffering from cashflow disruption brought about by the turbulence resulting from Covid-19. The programme is open to companies who make a "material contribution to the UK economy" and had, prior to March 1 2020, a short term rating of investment grade, or financial health equivalent to an investment grade rating.

|

|

Predictions that the Covid-19 bond market could top $100 billion by the end of 2020 do not seem so farfetched |

|

|

CPs issued under the CCFF must be: in sterling; with a maturity of between one week and 12 months; issued directly into Euroclear and/or Clearstream; and not be complex (no non-standard features). However, in contrast to the PEPP and indeed the BoE's own £200 million ($248 million) asset purchase programme – which operate predominantly in the secondary market to increase liquidity and support pricing – the Covid-19 Corporate Finance Facility (CCFF) provides direct support to firms by purchasing their securities in the primary market upon issuance via a dealer. Additionally, the BoE has confirmed that CP may be issued using International Capital Market Association (ICMA) euro CP templates, now available also to non-members through the ICMA Primary Market Handbook. In practice, this means that CP programmes can be quickly established to participate in the CCFF in as little as two to three weeks.

On June 4, the BoE released the first of its new weekly updates detailing drawings under the CCFF. In the latest of these, reporting to close 1 July, 188 businesses were approved as eligible to access the CCFF, the facility was supporting £17.6 billion (less redemptions) of lending to 62 businesses, and had approved for CCFF issuance a nominal sum of £79.1 billion. A further 82 businesses had been approved as eligible in principle but were still awaiting full approval for CCFF issuance.

US Federal Reserve's Commercial Paper Funding Facility

Like the UK's CCFF, the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) provides a liquidity backstop to US issuers of commercial paper, including municipalities, by purchasing CP directly from eligible issuers (defined for purposes of the CFPP as US issuers of commercial paper, including US issuers with a non-US parent company). As already touched upon, the CP market is typically used for the financing of short-term liabilities and so is a critical source of funding for some of the largest companies in the world.

|

|

There is a separate group of issuers that are using the convertible bond market opportunistically to fund growth |

|

|

In mid-March, the US CP market was effectively frozen as, due to the adverse effect of Covid-19 on global financial markets, investors had become reluctant to purchase CP. As a result, mirroring what was happening in other jurisdictions, interest rates on longer-term CP (such as with a maturity of three months) surged to levels not seen since the financial crisis of 2008, with a 90-day A2/P2 non-financial rate peak of 3.87% reached on March 19 (Source: Federal Reserve Board 2020). Many firms consequently reported being unable to issue CP with a term of longer than a week, thus increasing their rollover risk and reducing the ability of the CP market to support their operations.

In response, the US Federal Reserve Board established the $10 billion CPFF to cover three-month unsecured and asset-backed US dollar-denominated CP from issuers rated at least A1/P1/F1 as at March 17 (with one-time sales permitted to issuers who were subsequently downgraded no lower than A2/P2/F2). The introduction of the facility brought much-needed relief. The Federal Reserve reported that in its first month of operation, to May 14, the CPFF purchased more than $4.2 billion of eligible US dollar-denominated commercial paper. It also stimulated the market such that borrowing costs dropped (for example, the 90-day A2/P2 non-financial rate had fallen to 0.85% by May 14 from its 3.87% peak on March 19 – Source: Federal Reserve Board 2020) and issuers of CP were able to avail themselves of debt of longer maturities; up to 270 days.

Social bonds softening the blow

In the whole of 2019, only $13 billion of social bonds were issued globally, according to Sustainalytics (compared to $257 billion of green bonds). Even when sustainability bonds, which include a mix of social and green use of proceeds, are included in this figure, they still only account for 20% of all green, social and sustainability (GSS) bond issuances in 2019. However, as it becomes clear that more funding is needed for economic recovery than even the strongest national efforts can provide, investors have a key role to play, and social bonds could provide them with the perfect excuse to get involved.

The ICMA Quarterly Report for Q2 2020 identified social bonds as "a readily actionable response for the market to contribute to the response to the economic consequences of the Covid-19 crisis" and it is this widely-held opinion that is seeing social bonds growing in stature. They are being increasingly viewed as essential to contain the economic fallout of Covid-19 and to build resilience against future shocks by supporting healthcare, employment and housing. Indeed, looking to encourage not just the raft of usual social bond issuers to market (international financial institutions and development banks), the International Finance Corporation (IFC) – itself a key player in the social bond market – has published case studies that highlight how issuers from various industries may also use social bonds to raise financing that will go towards addressing social issues that have emerged as a consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Further, several major stock exchanges have now agreed to waive listing fees for social and sustainable debt instruments that are issued to address Covid-19, including the London and Luxembourg Stock Exchanges, and exchanges run by Nasdaq in Copenhagen, Helsinki and Stockholm. In addition, though up until now the Green and Social Bond Principles have strongly encouraged issuers to publish a framework document before, or at least at the same time as, issuing bonds, they are now considering allowing issuers to publish this framework up to a year after issuance. This – which will be familiar to investors involved with green bonds – could prove a useful innovation, enabling issuers to come to market quicker, utilising a miniature framework in their use of proceeds disclosure instead of the usual few lines referring investors back to a presale framework for this information.

The effects of these measures and the fact that issuance of social bonds broadens the options for investors with ESG investment mandates while simultaneously addressing socioeconomic issues that other capital market mechanisms do not, means that social bonds provide the perfect fit to our present niche problems.

Recent, big-ticket issuances certainly support this. In the first four months of 2020, Ecuador became the first country to issue a sovereign social bond, backed by a guarantee from the InterAmerican Development Bank, to support affordable housing; the IFC raised $1 billion through its three-year social bond; Bank of China issued a dual currency social bond raising HKD4 billion ($516 million) and MOP1 billion ($125.3 million), respectively; the African Development Bank launched a $3 billion Fight Covid-19 social bond in April, the world's largest dollar-denominated social bond transaction, as well as an SEK2.5 billion ($268.2 million) domestic social bond. In Europe, the Council of Europe Development Bank, the Nordic Investment Bank, and Italy's Cassa Depositi e Prestiti each announced Covid-19 social bonds focused on healthcare and direct lending for small businesses.

Perhaps more tellingly, though, corporates have also jumped onto the bandwagon. The first Covid-19 social bond issued by a corporate bank was issued by the Macau SAR branch of Bank of China in late February, raising more than $600 million to support Macau's small and medium enterprises. In the US, Bank of America came to market in early May with a $1 billion four-year Covid-19 bond to fund lending to hospitals, nursing facilities and healthcare manufacturers, among others, as they try to tackle the pandemic.

In Europe, French public-sector lender Caffil issued a €1 billion, five-year social bond to finance public hospitals affected by the pandemic in April that was more than four times oversubscribed – the highest rate of any bond issue since 2013 – and had the lowest coupon (0.01%) ever paid on a transaction of similar size, while Spain's Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria became the first European corporate bank to launch a social bond in May, an inaugural €1 billion with proceeds to mitigate "the economic and social impact caused by the Covid-19 pandemic". In the face of such demand, predictions that the Covid-19 bond market could top $100 billion by the end of 2020 do not seem so farfetched. Likewise, we can certainly expect that social bond issuances will account for a much larger slice of the GSS pie in 2020 than the meagre five percent they enjoyed in 2019.

Q1-2 2019 Hybrid Issuances

Source: Refinitiv

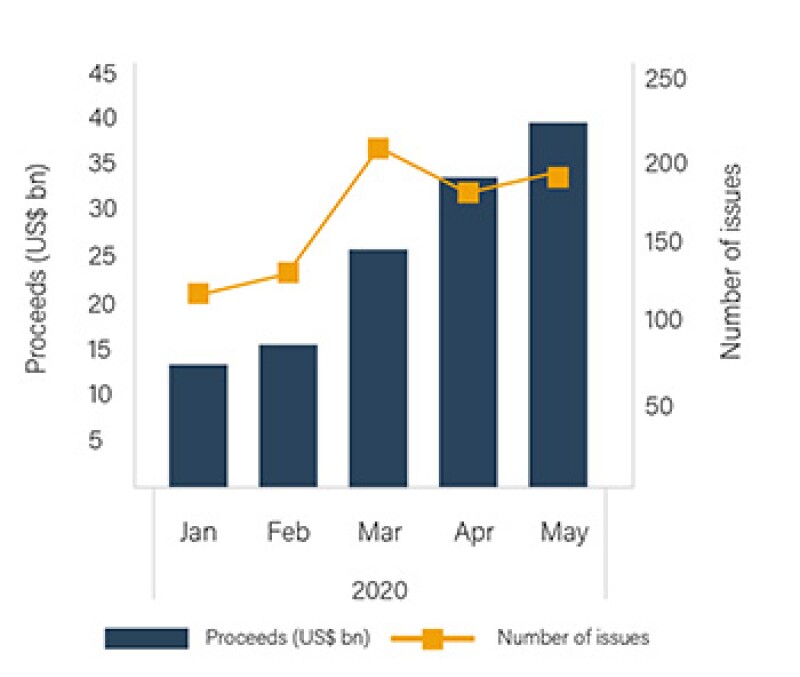

Q1-2 2020 Hybrid Issuances

Source: Refinitiv

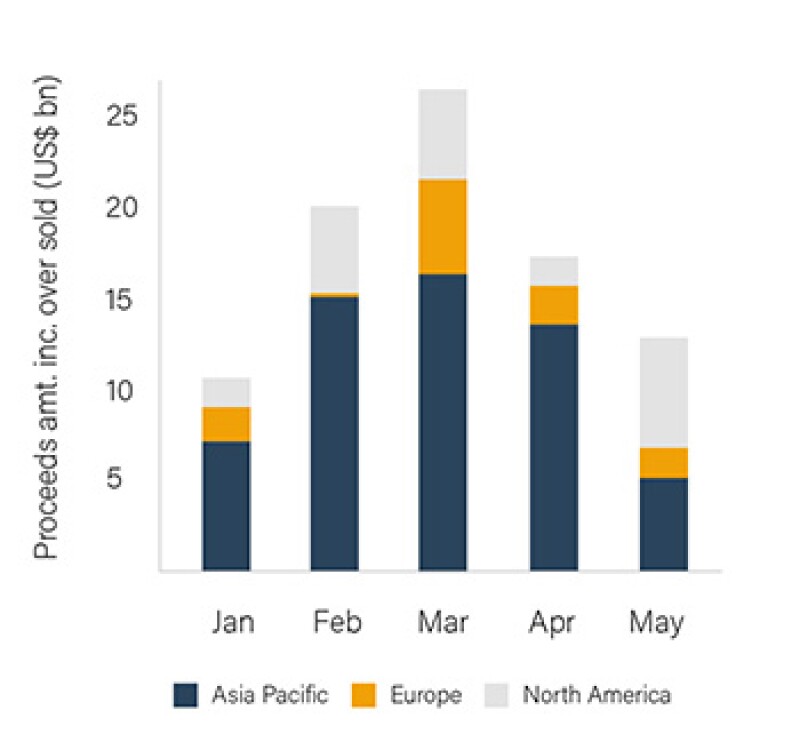

2019 Regional Breakdown

Source: Refinitiv

2020 Regional Breakdown

Source: Refinitiv

The re-emergence of hybrid securities

The first convertible bonds were issued in the late 19th century by US railroad companies. A somewhat pioneering spirit in the face of adversity still underpins the hybrid security market today, as volatility in the markets, rising interest rates and an uncertain economic climate are often key drivers in the popularity of hybrid bonds.

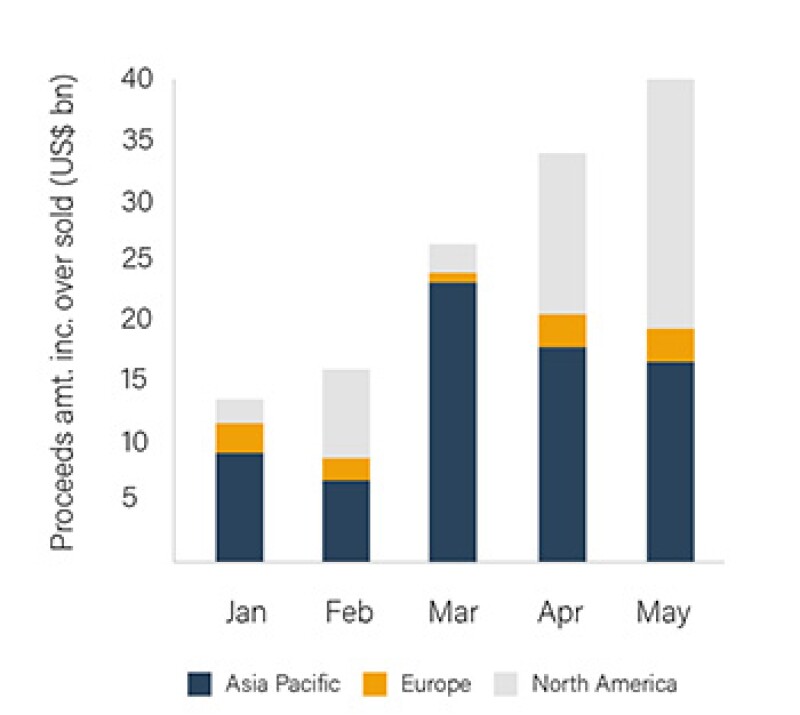

For example, as the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic started to be felt across financial markets and global business during the latter portion of Q1 2020, both the total proceeds and the number of hybrid bond offerings increased significantly, almost doubling from proceeds of $13.6 billion from 117 issues in January 2020 to proceeds of $26.3 billion from 210 issues in March 2020. Similar to the trend we have seen for follow-on offerings, as the economic fallout has started to show, companies have looked to the capital markets' willingness to fund larger hybrid deal sizes. Iberdrola, for example, attracted such demand for its initially €150 million tap in late May that it increased the issue amount by two-thirds to €249 million. As a result, in contrast to the deal flow in 2019, where numbers and value dropped away in Q2, Q2 2020 started very strongly, with $34.3 billion raised in April 2020, a 97% year-on-year increase. It showed no signs of stopping through May either, with $39.9 billion raised: an incredible 308% year-on-year increase.

Hybrid securities, such as convertible and exchangeable bonds, combine features of both equity and debt by providing a right to convert the bond into equity. This conversion right enables investors to benefit from an equity upside if share prices rise, while enjoying the downside protection of coupon payments and repayment of principal at maturity if the bond is not redeemed, converted or sold.

In the current climate, where share prices of many companies have plunged precipitously just as a few have risen sharply, we are seeing two distinct kinds of issuer coming to market. Companies in sectors presently heavily affected by Covid-19, like oil, retail, travel and leisure, which have stretched credit profiles due to the effects of the pandemic yet are desperate to raise cash, are joining the group more traditionally comprised of lower-rated, high-growth issuers. These issuers are able to offer hybrid security issuances with generally lower interest rates than would be expected were they offering traditional non-convertible bonds. In Europe, many of the companies that have issued recently fall into this first group, such as cruise line operator Carnival, Spanish and British oil majors Repsol and BP, Spanish IT supplier Amadeus, and Swiss duty free operator Dufry.

In addition, there is a separate group of issuers that are using the convertible bond market opportunistically to fund growth and opportunities because the terms are very attractive and/or their businesses are positioned to do well out of the crisis. Nexi, the Italian payments company, falls squarely in this latter category even though it is itself a high yield issuer. Others companies that have tapped the markets after benefitting from the pandemic include New York Stock Exchange-listed Sea, the Singaporean online gaming company, whose share price surged after it reported strong first-quarter earnings. Similarly, Slack Technologies, the enterprise messaging and collaboration platform, which added 9,000 new paid customers in the first two months of Q1 2020 – compared to 5,000 new customers in each of the prior two full quarters – upsized its $600 million convertible offering to $750 million based on demand in April.

Whether the current market dislocation we are experiencing is short-lived or, as most expect, the start of a more prolonged downturn, the wave of issuance that we are seeing across the regions is expected to continue, with the US leading the way. April, for instance, was the strongest month for US convertible bonds since March 2007, with issuances of $13.5 billion buoyed by the likes of Southwest Airlines and Carnival coming to market with the second and third biggest deals of the year. May numbers then blew this out of the water by presenting the highest monthly volume of hybrid debt issuances on record: $20.6 billion.

Recovery and renewal

Companies and individuals have had to become more resilient in response to Covid-19, adapting to the changing landscape. While government intervention schemes have unarguably thrown a lifeline to the global economy, as we move into the phases of recovery and renewal, the capital markets present an efficient and viable solution to mitigate the uncertainties and pave a way forward. However, though the debt capital markets are very attractive to corporates, providing quick and effective sources of liquidity, if used in isolation, there is a very real risk that heightened debt could have a negative impact on companies' credit ratings and on their ability to obtain new funding going forward.

As such, if companies are to start planning now for a future without the burden of too much leverage, the ideal solution would see a proper balance, drawing funding from both the debt and equity markets.

Please stay up to date with further developments at Baker McKenzie's Beyond COVID-19 Resource Center.

|

Ashok Lalwani Partner Baker McKenzie, Singapore |

|

Duncan McGrath Partner Baker McKenzie, Sydney |

|

José Moran Partner Baker McKenzie, Chicago |

|

Roy Pearce Partner Baker McKenzie, London |

|

Lisa Nielsen Board Senior Knowledge Lawyer Baker McKenzie, London |