2020 proved to be a year of two halves in China. In Q1 and Q2, the market suffered the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in a dramatic way. However, Q3 and Q4 proved surprisingly resilient, and saw the return of significant M&A activity – whether it was through restarted prospective deals or new opportunities.

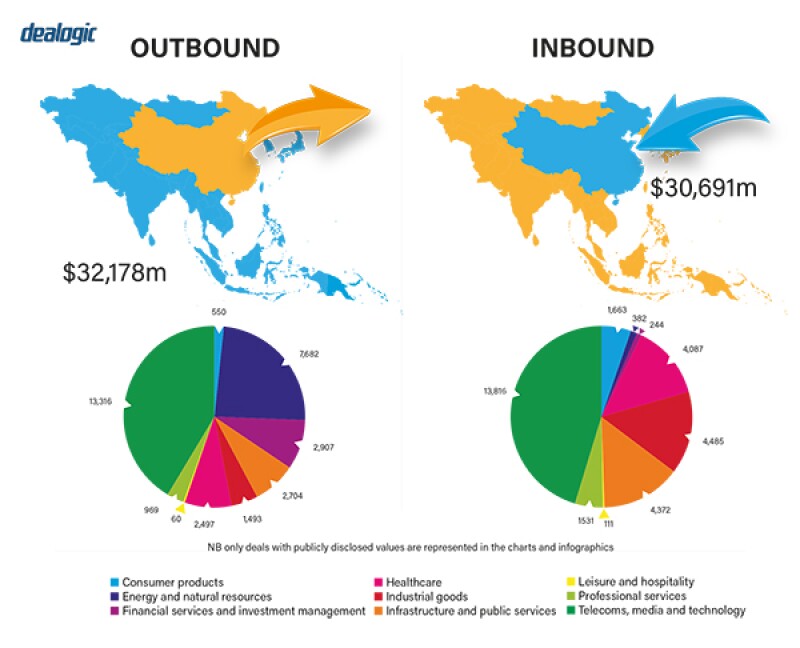

According to public statistics, Chinese M&A deals increased by 30% to $734 billion in 2020, the highest since 2016. The increase was largely driven by strong state and government investment support on domestic M&A. On the other hand, as expected, cross-border M&A deals decreased greatly.

In a notable transaction of 2020, technology manufacturer Wingtech acquired Nexperia for RMB 26.8 billion (approximately $4.15 billion), marking the largest M&A deal in the Chinese semiconductor sector. Apart from Wingtech's acquisition, there has been a few other large-scale transnational M&A deals initiated by Chinese companies in the semiconductor sector during 2020.

Like in China, the global semiconductor industry also had a successful end to 2020. In just four months from July to October, five major M&A deals have been ushered in, of which three can be ranked among the top five semiconductor deals in the world. These cases include Analog Devices' (ADI) acquisition of Maxim for $21 billion, as well as NVIDIA's planned purchase of Arm for $40 billion.

With several large companies such as Huawei and SMIC being listed on US export control entity list, and foreign regulatory agencies' barriers on the acquisition of semiconductor business from Chinese buyers, the market witnessed more incentive policies from the Chinese government on promoting semiconductor development in China and domestic investment by state-owned industrial funds, rather than M&A deals initiated by companies. It is expected that the political and economic impact will continue to be a key factor of the low volume of cross-border Chinese M&A business in the semiconductor sector.

COVID-19 and recovery plans

Although deal value suffered a sharp dip due to the COVID-19 lockdown in February, deal values held up, bouncing back in the second half of 2020. The increase in deal values was driven by strong government participation in both domestic strategic and private equity (PE) deals – especially via state-owned funds – mitigated by a steep decline in cross-border M&A.

Private capital has been very proactive in the Chinese M&A market in 2020. Both PE deal values and volumes hit a record high caused by major state and government sponsored capital injections, especially in the industrials, technology, consumer and healthcare sectors. The formation of a mature financial investor environment is expected to be a key driver of long-term growth in China's M&A market.

|

|

The law in China continues to rapidly evolve on guidelines related to environmental, social and governance (ESG) |

|

|

Domestic M&A rebounded to levels last seen in 2017, driven by strong state-involvement and support for various banks and securities companies. Meanwhile, China outbound M&A was hit by the COVID-19 situation, as well as political factors which together made cross-border deals very difficult, especially into developed markets such as the US and Europe. The deal values of outbound M&A were the lowest since 2010.

The pandemic, and the potential for further waves of infection and consequential disruption, has caused parties to focus more closely than ever on pre-closing covenants in transaction documents. A balance has to be struck between a seller wishing to reserve sufficient flexibility to react nimbly to changes in the operating environment, and a buyer wishing to ensure that the target business is not unnecessarily adversely affected by how it is run during the period between signing and closing.

Buyers may also seek a right to walk away in the event of a further wave of infection and associated business interruption, but sellers are likely to resist any such rights to include so-called material adverse change (MAC) clauses. The allocation of MAC risk between parties is likely to entail detailed negotiation of each deal.

Legislation and policy changes

There is no single law or regulation specifically regulating M&A in China. A transaction may involve many laws and regulations. Chinese company law may be relevant when designing the corporate structure of the target company, while the securities law and its supporting regulations may come into play in a public M&A transaction. Employment law and employment contract law may come into play when employees need to be transferred in the transaction, while tax law is always relevant.

Foreign exchange policy and regulation is important when payment of the deal needs to be made cross-border. Antitrust law may be relevant if a deal meets a certain threshold triggering a regulatory requirement to make a filing. The newly enacted Chinse Civil Code may also have some indirect impact on M&A transactions.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) regulation has become an increasingly important consideration for cross-border M&A for Chinese companies' oversea investments, against a backdrop of amplified protectionist rhetoric. A number of countries were moving towards stricter public interest and FDI scrutiny of transactions.

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, these trends have been accelerated as governments have sought to move quickly to protect businesses affected by the economic fall-out, in light of concerns surrounding opportunistic acquisitions by foreign buyers.

Against this backdrop, there has been a raft of significant amendments to existing FDI regimes taking effect in 2020, including the notable expansion of the jurisdiction of Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) in the US, and a tightening of notification thresholds in Japan.

Some amendments are directly tied to the impact of the pandemic. For example, the express inclusion of healthcare as a sector covered by FDI regulation in many jurisdictions including Spain, Italy and Germany, and the reduction of financial thresholds, including notably to zero in Australia, so as to effectively make all FDI reviewable for the duration of the pandemic.

On December 19 2020, China's National Development and Reform Commission and the Ministry of Commerce jointly issued the 'Measures for the Security Review of Foreign Investment' (Security Review Measures), which came into effect on January 18 2021. The Security Review Measures stipulates types of investment that may be subject to national security review in China, the review procedures and time limit.

If a foreign company intends to carry out M&A in China in investment areas that require pre-declaration, and after the company has filed for security review in accordance with regulations, if the review government agency decides to prohibit investment, the merger transaction cannot proceed. Foreign investors who fail to declare in accordance with regulations, falsely provide materials or conceal information declarations may be ordered to correct, dispose of equity or assets within a time limit.

Market norms

The law in China continues to rapidly evolve on guidelines related to environmental, social and governance (ESG). There is a growing need for buyers to examine carefully whether a target is exposed to ESG risks, understand whether it will meet stakeholder expectations and regulatory requirements in the future and, particularly with respect to PE or opportunistic buyers, ensure that the value of the investment is preserved and a clean and responsible exit in due course is possible. Fulsome ESG due diligence can also contribute to successful deal-making by helping acquirers to identify potential difficulties that may increase the cost of integration and challenge performance in the long term.

|

|

Chinese M&A deals increased by 30% to $734 billion in 2020, the highest since 2016 |

|

|

Post-closing integrations of the acquired company are often neglected in Chinese M&A deals and should be handled with more care. The 'closing date' is often seen as the crescendo of a purchase. Months and sometimes years pass between initial discussions and the closing of a deal. The weeks leading up to the closing are high paced and stressful, coupled with exhaustive checklists barrelling toward completion. The parties breathe a sigh of relief when the closing meeting concludes, and both parties leave – for one of them, the transaction likely marks the end of the road. However, on the other side, closing is just the beginning.

The acquirer will generally want to integrate the two businesses to cut costs and generate value for its shareholders. Bringing together businesses with different contractual relationships, histories, and cultures inevitably poses substantial challenges. However, the majority of acquisitions fail to meet pre-deal expectations. Deals fail for several reasons but generally fall within a few broad categories: missed targets, poor performance in the core business, or an unintended loss of essential people. Therefore, having a proper post-deal integration plan in mind is vital because inexperienced and ineffective dealmakers often fail to plan accordingly for this period following closing.

Technology is playing an increasingly important in China's M&A transactions, mostly as tools to accelerate the process of deal-making process. In most major M&A transactions, sellers usually upload relevant documents into a virtual data room for buyers to conduct due diligence. Due to the COVID-19, online conference systems, virtual site visits and data storage technology are increasingly used during the negotiation and execution of an M&A deal.

Public M&A

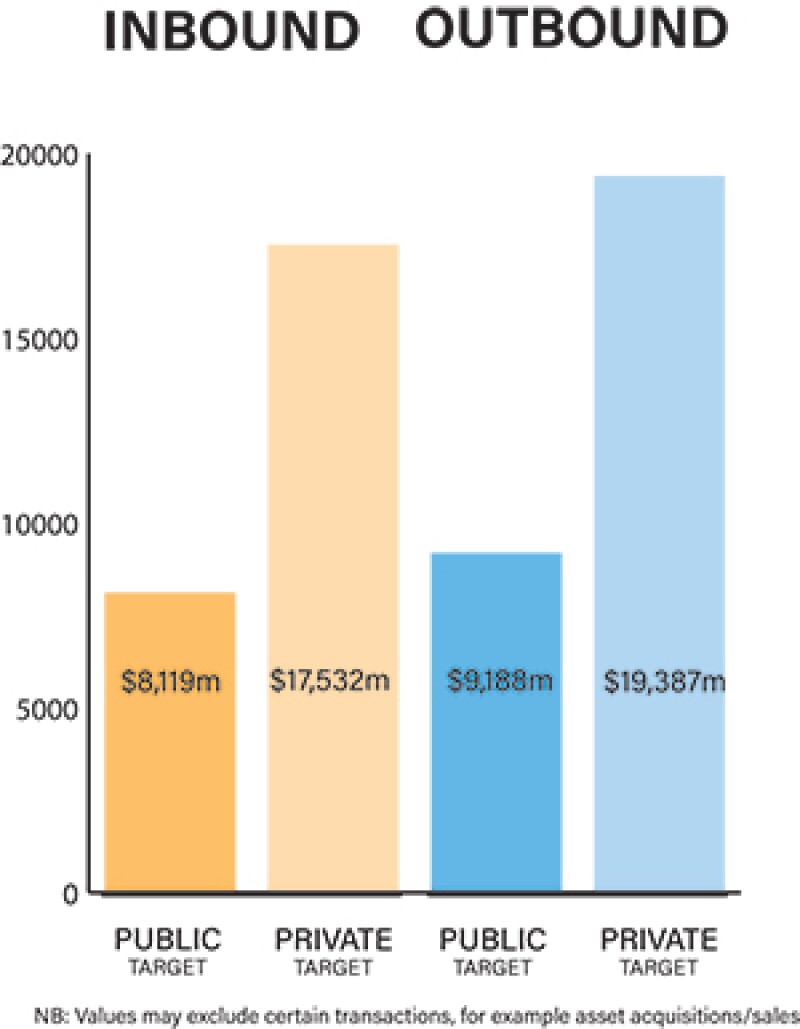

In public transactions, obtaining a certain percentage of equity is the key to gaining control of a listed company. The acquirer should be the largest shareholder of the listed company and hold at least 20% of the shares after the completion of the control acquisition of the listed company.

Therefore, it is a key factor for the acquirer to consider the method of obtaining the sufficient percentage of shares. In general, the acquirer may purchase stocks through: (a) agreement from existing shareholders of the listed company; (b) purchase from the secondary market; or (c) tender offer. It is important to note that the existing shareholder of a listed company, either being the actual controller of the listed company or management of the company, is likely to subject to restricted share trade period as well as restrictions on percentage of shares he/she may trade in a certain period.

The acquirer is required to publicly disclose all its necessary information during the public takeover. The purchase price, the purchase price payment method, the offer validity/commitment period, the change of the offer and the cancellation of the offer are usually attached to a public takeover offer.

Break fees are usually agreed as liquidated damages in a public M&A transaction in China. The amount of the liquidated damages may vary in different deals, depending on negotiation leverage and the transaction price. In practice, liquidated damages for breaching a public M&A transaction deal are around 20% of the transaction price, while the existing laws and regulations stipulate that the liquidated damages shall not exceed 30%.

Private M&A

Locked-box mechanisms, completion accounts and earn-outs are all common mechanisms for consideration in private M&A transactions. In some cases, a locked-box mechanism is combined with earn-outs calculation by requiring the equity seller to bear certain operational risks in order to protect the buyers' interests. In terms of protection mechanism, escrow accounts are commonly used in M&A transactions in China, while indemnity insurance is only used in major M&A deals.

|

|

In 2020, PEs continued to face pressure to sell resulting in a record number of exits and PE-backed IPOs |

|

|

Parties in a private takeover may agree on different conditions based on the nature of the transaction, the needs of both parties and the negotiation leverage. It is uncommon to provide for a foreign governing law and/or jurisdiction in private M&A share purchase agreements, unless both parties are foreign enterprises and prefer foreign jurisdictions or the target company is located in a foreign jurisdiction.

There are many ways for a company to exit after an acquisition. IPOs, share transfers, shares buy-backs and liquidation are all feasible and common exit plans for investors in China. Before the execution of a M&A transaction documents, parties usually have a specific goal for the future of the target company. In addition, these exit options should be carefully and clearly listed in the transaction document to prevent any dispute in the future.

In 2020, PEs continued to face pressure to sell resulting in a record number of exits and PE-backed IPOs. The IPO market in 2020 was booming in China, underpinned by the favourable changes in Chinese securities regulations and high asset prices generally.

Looking ahead

Looking to 2021, the M&A market in China is likely to continue to have a domestic theme supported by state-owned companies or industrial funds. The effects of COVID-19 and other material uncertainties around trade and geopolitical relations will continue to impact cross-border M&A activities.

In general, there may be some increases in Chinese M&A overall in 2021 largely driven by domestic, PE and state-backed investment.

Click here to read all chapters from the IFLR M&A Report 2021

Carl Li

Senior partner

AllBright Law Offices

T: +86 138 1668 1760

Carl Li is a senior partner at AllBright Law Offices, primarily working from the Shanghai office. His practice areas include M&A, PE funds, FDI and compliance.

Carl has provided comprehensive legal support to the Chinese part of multiple renowned transnational group companies' global reorganisations, separations, and mergers. He has assisted various well-known funds in establishing domestic and overseas private funds, and acts as the legal counsel to foreign enterprises in China, providing comprehensive legal support to the establishment of new projects or capital. In addition, he has extensive experience in sectors including the medical, health, and life science industries.

Carl graduated with a LLM from Renmin University Law School and completed the executive MBA programme at China Europe International Business School. He has been a visiting scholar at University of Maryland College Park, and trained at Harvard Law School.