Despite the lingering effects of Covid-19 both locally and globally, the M&A market in Slovenia has been very active lately and investors’ sentiment continues to be optimistic. After the initial shock in 2020 when most transactions were temporarily put on hold, there has been a recovery of confidence in the economy in 2021, in which we observed as much M&A activity as ever. This will continue in 2022.

On the legal side, the foreign direct investment (FDI) screening regulation, adopted in 2020, requires mandatory filings to be made by foreign investors. The FDI legislation is interpreted quite broadly by the authorities and as a result catches many more deals than would normally be expected (e.g. EU investments, including domestic Slovenian investments). A notable hot topic is the limitations on upstreaming and debt push down that have been heavily scrutinised in Slovenia lately and are subject to an increasingly stringent (and developing) case law, with further decisions handed down in 2021 which tighten the wriggle room.

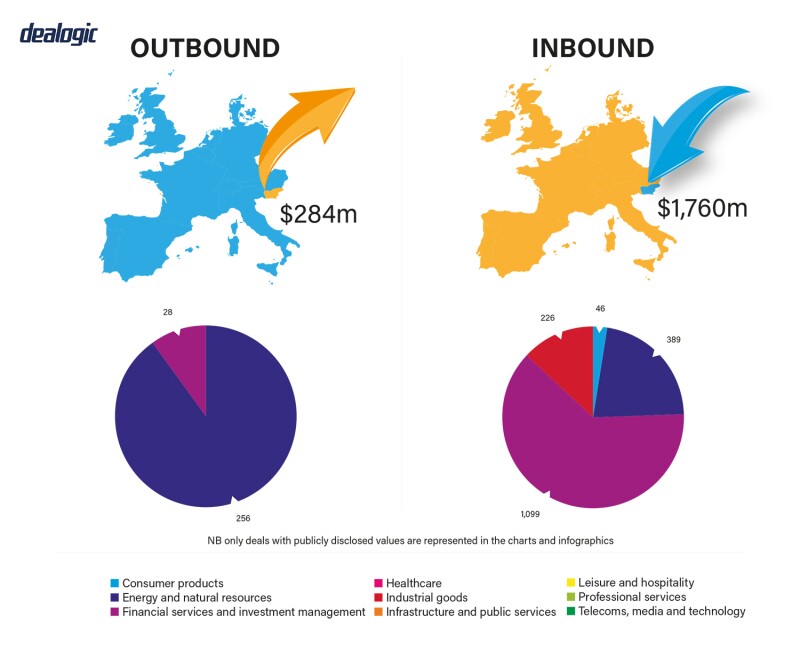

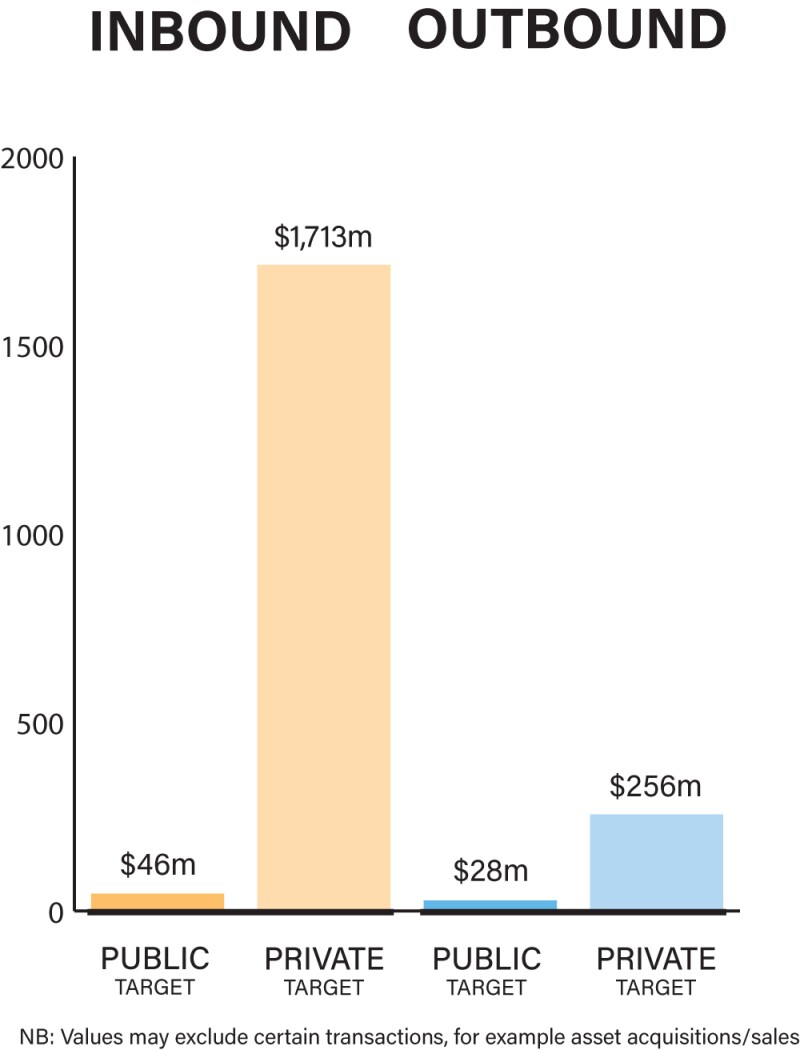

The Slovenian market is strongly driven by private M&A transactions. Large public transactions have been scarce in the post-privatisation era, as the focus has shifted to the consolidation and reorganisation of previously acquired businesses.

Notable recent privatisations include the sale by the Slovenian Sovereign Holding of Abanka Bank to Apollo and a consequent merger with Nova KBM Bank, and the sale of the (indirect) investment in BIA Separations to Sartorius (which was then subject to court proceedings as political climate thought the deal had not been advantageous to the Slovenian state). Additionally, the establishment of a joint venture of Slovenske železnice and Czech EP Logistic International (EPLI) was closed in January 2022.

Significant trends in the market include exits by domestic entrepreneurs from their companies that were established in the late 1990s/early 2000s and have now reached the maturity stage, as well as cross-border joint ventures in various industries. Slovenia has seen significant banking and investment sector consolidation in the past couple of years – in 2021, Hungarian OTP Bank, which already owns SKB banka, acquired Nova KBM (combining formerly separated Nova KBM and Abanka; the deal is pending regulatory clearance) and Gorenjska banka acquired the Slovenian Sberbank subsidiary.

Globally, the global consolidation in the paints and coatings sector was reflected in the sale of JUB, the oldest Slovenian paint manufacturer with a presence in central and eastern Europe and the Balkans, which attracted significant interest. The JUB group was sold to Australian Dulux (owned by Nippon Paint). The transaction was particularly complex as it included more than 200 sellers (mostly natural persons), complex selling restrictions and takeover protections.

Slovenia is particularly strong in the IT and technology sector where M&A activity has been robust in the past and has continued to be in 2021; we expect this trend to continue in 2022. One of the more notable transactions included Inelo Group’s acquisition of CVS mobile, a provider of telematics solutions, creating the foremost telematics provider in the world. Slovenia seems to be a very successful exporter of knowledge in the IT sector and we expect the M&A activity to strengthen in 2022.

Furthermore, despite the unclear FDI legislation we have not encountered any major issues in this respect when advising on M&A transactions.

Economic recovery plans

As mentioned above, in 2021 Slovenia joined the global trend of a booming M&A market, particularly in comparison to 2020 when most transactions were either stopped or put on hold. Takeover activity was extremely dynamic, even compared to the financial crisis about a decade ago. The largest acquisitions in 2021 in terms of value were in the banking sector and manufacturing.

The largest transaction in Slovenia was the purchase of Nova KBM as the second largest banking group in Slovenia (combining formerly separated Nova KBM and Abanka) by Hungarian OTP Bank, followed by the sale of OMV’s service stations business to MOL. The sale of JUB, a Slovenian paint manufacturer, to Australian Dulux (owned by Japanese corporation Nippon Paint), was the third largest transaction in Slovenia in 2021.

Nevertheless, Covid-19 continues to have an impact on the M&A landscape, most significantly on the response and adaptation of the parties to the uncertainty of the possible long-term effects of the pandemic. It has become customary to include in M&A transactions appropriate limitation language considering the effects of Covid-19 on deals and to review carefully the receipt of any Covid-19 related state aid in the due diligence process as well as profit distributions and management bonuses. These are restricted in certain cases and can trigger refund obligations for all Covid-19 related state aid (which can be in the millions).

|

|

“Slovenia seems to be a very successful exporter of knowledge in the IT sector and we expect the M&A activity to strengthen in 2022” |

|

|

All indications point to another dynamic year in the M&A market and the economic optimism remains relatively high. Several transactions have already been announced or are ongoing in various sectors. Furthermore, there has been renewed speculation regarding the sale of Telekom, Slovenia’s largest public telecommunications operator. According to information gathered by the Bank of Slovenia, Slovenian companies with FDI tend to have higher capital returns, higher wages and value added per employee. This is confirmed by experience and it is likely to (further) stimulate the M&A market activities in the future.

While several major transactions in recent years have involved institutional investors – mostly private equity (PE) funds – investing in Slovenian companies, investments by strategic investors have recently regained significant traction (Dulux as strategic global acquirer and JUB as strategic global target, for example).

Corporate restructuring and reorganisations do not yet seem to be at the forefront of deal generating, but we expect that once the full effects of the Covid-19 pandemic materialise (e.g. non-performing bank loans, distressed and non-core assets). M&A disputes are not common in Slovenia and Covid-19 related implications have not been witnessed in respect of M&A, although there have been Covid-19 disputes in Slovenia generally (particularly with respect to the payment of rent for business premises).

Financial investors have been, and continue to be, acting in the market as deal originators, primarily looking for undervalued local businesses with significant growth and expansion potential, and with a particular focus on the IT sector.

Slovenia has a strong entrepreneurship base and many local companies are targeted by financial investors looking to acquire them and exit after consolidation with other players in global markets. In 2021, we have also seen special purpose acquisition companies enter the Slovenian space.

Legislation and policy changes

M&A transactions are governed by a number of regulations, depending on the deal structure and other criteria. Most share deals in Slovenia involve either limited liability companies (družbe z omejeno odgovornostjo) or joint-stock companies (delniške družbe), both of which are regulated by the Companies Act (Zakon o gospodarskih družbah, ZGD-1). The Companies Act also regulates mergers, demergers and spin-offs of these companies.

Pursuant to the Companies Act, sale and purchase agreements for shares in limited liability companies are entered into in the form of a notarial deed (the same requirement also applies to powers of attorney to enter into such agreements). The non-selling shareholders have the right of first refusal in such transactions (which may be waived). Additionally, the articles of association of each individual company may prescribe that a permission by the majority or all of the shareholders is required for the transfer, which may hinder some transactions. The transfer of shares in limited liability companies is registered with the court (business) register upon the transaction.

Sale and purchase agreements for stocks in joint-stock companies do not need to be entered into in the form of a notarial deed. No statutory right of first refusal of the non-selling shareholders applies to joint-stock companies, but the charters of the companies may stipulate that permission by the company (e.g. its management or supervisory bodies) is a prerequisite for the transfer of shares. The legally permitted grounds for the refusal to issue the permission are significantly more limited for public than for private joint-stock companies, and different consequences apply to these companies if no permission had been obtained before the transfer.

Asset deals are regulated in the Companies Act and Obligations Code (Obligacijski zakonik, OZ). While the sale of assets is typically agreed in a single master agreement, additional transactions need to be performed for the transfer of individual types of assets. A significant provision with regard to asset deals is Article 433 of the Obligations Code, which stipulates that a person to whom a property unit (in full or in part) passes under the agreement (e.g. the buyer) shall be liable, in addition to, and jointly and severally with, the previous holder (e.g. the seller) for any debts relating to that property up to the value of that property unit’s assets. This liability of the buyer (albeit limited) may in some cases be a deterrent for investors wishing to enter into an asset deal.

Takeovers of public and certain private joint-stock companies are regulated in the Takeovers Act (Zakon o prevzemih, ZPre-1), which prescribes rules for both mandatory and non-mandatory (voluntary) takeovers. The applicable threshold triggering a mandatory takeover bid of the shares of the target company by an individual shareholder or shareholders acting in concert is one-third of voting rights in that company.

Shareholders under the obligation to submit a mandatory takeover who fail to do so will have their voting rights suspended and may not vote at the general meeting of the company until they submit a successful bid. Compliance with the Takeovers Act is monitored and breaches are sanctioned by the Securities Market Agency (Agencija za trg vrednostnih papirjev). It is important to note that in Slovenia, takeover legislation applies to any joint-stock company that has either over 250 shareholders or over €4 million (approximately $4.8 million) of total equity, which is a relatively low bar.

M&A transactions exceeding certain thresholds are also subject to clearance by the Competition Agency (Agencija za varstvo konkurence) pursuant to the Prevention of Restriction of Competition Act (Zakon o preprečevanju omejevanja konkurence, ZPOmK-1) or the European Commission pursuant to the applicable EU regulations.

Transactions have to be notified to the Competition Agency if (cumulatively) the combined Slovenian turnover of the parties to the transaction (with affiliates) exceeds €35 million and the annual turnover of the acquired company (with affiliates, excluding the seller and its affiliates) on the Slovenian market exceeded €1 million in the previous financial year. Additionally, the Competition Agency may also request the transaction to be notified if the parties to the transaction (with affiliates) hold a combined market share of over 60% in Slovenia.

Since May 31 2020, most M&A transactions are also subject to FDI screening procedure by the Ministry of Economic Development and Technology (Ministrstvo za gospodarski razvoj in tehnologijo). While the screening was introduced as part of Covid-19 related legislation, i.e. in the Act Determining the Intervention Measures to Mitigate and Remedy the Consequences of the Covid-19 Epidemic (Zakon o interventnih ukrepih za omilitev in odpravo posledic epidemije Covid-19, ZIUOOPE), its application is significantly broad and is not limited to the Covid-19 context. It is set to expire in 2023, but may be extended before expiration.

FDI filings are required for all foreign investments (including from EU investors) into critical infrastructure that could affect security or public order, in cases of acquisitions of 10% of the share capital or voting rights of the target in Slovenia. As the ministry has taken a significantly broad interpretation of investments falling under the screening regime, it has become customary for foreign investors to lodge the filings out of prudence in most cross-border transactions, regardless of the industry or transaction structure (and even when an indirect holding in the Slovenian company is obtained in the transaction). The parties entering into transactions should also consider that the ministry shall have the power to terminate the transaction and declare it void for five years after the transaction (i.e. retroactively), which is a risk that cannot be fully mitigated by the parties.

As mentioned above, due to uncertainty related to Covid-19 pandemic, the inclusion of contractual clauses considering the effects of Covid-19 on deals has become quite common. Environmental, sustainable and corporate governance-related topics have mostly had an impact on the scope of due diligence and representations and warranties, which has come to be expected, particularly from foreign investors. Apart from that, we have not observed any additional major transformation as regards the conduction of M&A transactions.

Market norms

Foreign investors entering the Slovenian market are sometimes surprised by the lack of precedents and established case law on M&A (although this is not uncommon in the region). This is primarily due to the customary market practice of clients to enter into arbitration agreements instead of leaving the cases to be adjudicated by the courts, and to settle disputes in private rather than in public view.

Further, as transfers of shares in limited liability companies (the predominant form in Slovenia) need to be entered into the court register upon the transaction, this often requires complex closing mechanics that need to be appropriately drafted in the deal documentation and includes certain risks that have to be taken into account.

Pursuant to Slovenian legislation, all the deal documentation (e.g. share and purchase agreements and articles of association) is in principle publicly available and either published online or easily accessible at the court register or the land registry. As the parties are generally hesitant to publicly disclose all the information on the deal, they ordinarily opt to enter into separate short-form documents for delivery to the court register that only contain a limited set of relevant information.

Contrary to the mandatory takeover regimes in larger economies, the rules in the Takeover Act do not only apply to public joint-stock companies, but also to joint-stock companies that are not listed if they have at least 250 shareholders or over €4 million of total equity. The mandatory takeover bid rules therefore apply to most potential targets in Slovenia that take the form of a joint-stock company.

One aspect of legislation that can be overlooked but may have significant consequences (fines of at least €80,000 and potential loss of voting rights) is adequate wet ink reporting of acquired voting rights thresholds and option and futures agreements (both to the market regulator and target companies).

Another frequently overlooked aspect is that the Slovenian workers’ co-determination legislation requires the parties of certain transactions (such as business transfers via asset deals or demergers) to notify the target workers’ representatives of the anticipated transaction at least 30 days before the decision for the transaction was adopted, and perform consultations with them, i.e. not before an agreement is closed, but before the decision is made to enter into the transaction.

A relic of an era of the transition of Slovenia into a market economy and private ownership at the beginning of the 1990s, this statute is often at odds with modern conceptions of corporate decision-making and deal progress. As it is not always entirely clear at what time the decision for the transaction was ‘adopted’, it is advisable that the parties are sufficiently cautious and make a timely notification.

It has been our experience that parties often underestimate the importance of adequate tax structuring advice at an early stage of an M&A transaction. This can have major implications for the yield by the selling shareholders (for example, income related to disposal of companies can be taxed between 0% and 27%, sometimes also as employment income which is taxed at effective rates exceeding 50%).

Failure to take tax matters into account from an early stage can materially affect the economics of the deal and can have major consequences for all parties involved. It is advisable for in-house tax experts to be regularly included in the deal structuring from the beginning.

Advisory companies in Slovenia, including law firms, have increasingly been relying on technology for assistance in M&A deals. This particularly applies to due diligence where artificial intelligence (AI) and other tools are being implemented in document review, which helps in simplifying the process and reducing costs. Examples include AI for due diligence processes and code to parse and process Slovenian real estate land registry excerpts which significantly reduces time and effort needed to analyse significant volumes of land registry data (which is the norm in Slovenia).

Public M&A

Public M&A is not widespread in Slovenia and most changes of control occur in the private market. In the public market, the key factor for a successful acquisition is the economic conditions of the offer, especially the purchase price and at times securing broad enough support for the deal.

Pursuant to the Takeovers Act, the price in the takeover bid may not be lower than the maximum price at which the acquirer acquired the shares of the target company in the 12 months prior to the publication of the bid. Generally, shareholders in competitive/hostile takeovers expect from the acquirer an above market price and are less willing to sell than in a friendly takeover.

Even where a takeover is mandated for a target company, typically block deals will be concluded in the lead up to the mandatory tender offer, and amicable takeovers are the norm because typically there will be takeover protections and restrictions put in place that will have to be removed in a consensual manner before a takeover can proceed. If a takeover is mandatory and unsuccessful, loss of voting rights would ensue making the investment effectively dead in the water. So care must be taken to avoid such consequences.

A takeover bid may only include the conditions stipulated in the Takeovers Act, which mainly relate to the mandatory clearance requirements or threshold for the bid to be successful. In mandatory takeovers, the Takeovers Act requires that the bidder conditions its bid on reaching a threshold of more than 50% of all voting shares. The voting rights from the shares of the bidder who is under the obligation to make the mandatory bid shall be suspended until a successful bid reaching that threshold is made.

Private M&A

As private M&A transactions are the norm in Slovenia, they are also most often subject to discussions on the legal instruments to be incorporated into the deals.

The choice of consideration mechanisms in private M&A transactions depends heavily on the sophistication and size of the transaction. The agreements on completion accounts impose a significant administrative and accounting/discrepancy resolution burden on the parties and are thus more common in large and complex deals and in particular in PE transactions. While a locked box is easier to execute and more often used in smaller transactions, this mechanism has also been used in some major cross-border transactions, more commonly with strategic investors.

Parties sometimes consider warranty and indemnity insurance but is typically not agreed on (it is generally considered as expensive and excessively limited in the risks covered by the fine print). Earn outs are more often used by PE funds than strategic and other investors, and do not often end up in the deal documentation as the sellers are unwilling to accept the uncertainty of economic performance of the company under the management of the new owner.

Agreements on escrow mechanisms are common in transactions with a small number of sellers (5% to 10% of the purchase price, for one to two years) and are ordinarily executed by public notaries and not banks. Arrangements whereby the sellers must continue with the firm following the sale are also increasingly common, especially in the IT sector.

The conditions attached to a private takeover offer are usually customary, without any peculiarities.

It is not common practice in to provide for a foreign governing law and/or jurisdiction in private M&A share purchase agreements. Using foreign governing law is much less common where shares in a Slovenian company are directly acquired; however, even in such case, many foreign investors opt for arbitration for resolving any disputes arising out of the transaction.

The large majority of exits in Slovenia happen through a sale of the company to a PE fund or a strategic partner. Initial public offerings (IPOs) and other capital market transactions are less common. The last major IPO in Slovenia was of NLB, the largest Slovenian bank, in 2018.

Looking ahead

The outlook for the M&A market in Slovenia is optimistic and further strong activity in 2022 is expected.

Similar trends as seen in the market over the last 12 months can be expected, particularly further exits from successful mid-size companies and cross-border joint venture agreements, including public and private deals.

It is also expected that PE funds that entered the Slovenian market in the mid-2010s will continue to consolidate their investments and gradually get ready for exit.

Click here to read all the chapters from the IFLR M&A Report 2022

Ožbej Merc

Partner

Jadek & Pensa

T: + 386 1 234 25 20

Ožbej Merc is a partner and head of the transaction department at Jadek & Pensa. He specialises in M&As, insolvency and restructuring, and banking and finance.

Ožbej has participated in most of the restructurings of large systems in Slovenia and has been providing advice on the most demanding M&A transactions and issues related to M&As.

Ožbej graduated from the Faculty of Law in Ljubljana and obtained an LL.M. from the University of Columbia in New York in 2005.

Nastja Merlak

Managing associate

Jadek & Pensa

T: + 386 1 234 25 20

E: nastja.merlak@jadek-pensa.si

Nastja Merlak is a managing associate at Jadek & Pensa who primarily advises clients on corporate law, insolvency law and banking and finance. She regularly participates in significant M&A transactions and restructurings.

Nastja graduated from the Faculty of Law in Ljubljana and obtained an LL.M. from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) in 2015.

Ana Gradišar Lužar

Associate

Jadek & Pensa

T: +386 1 234 25 20

E: ana.gradisar@jadek-pensa.si

Ana Gradišar Lužar is an associate at Jadek & Pensa. She mainly advises clients on M&A, insolvency law and restructuring, banking and finance, corporate law, real estate, construction and infrastructure.

Ana worked for an eminent Slovenian law firm before joining Jadek & Pensa. She worked mainly in the fields of commercial and corporate law, as well as actively participated in various due diligence reviews and M&A transactions.

Ana has a master’s degree from the University of Ljubljana Law School.