During the first half of 2021, M&A activity in Thailand was slow, with several transactions being pulled, delayed or put on hold due to the Covid-19 pandemic. However, there were signs of recovery during the second half of 2021, as the Thai government’s lockdown and travel restrictions were eased and business operators adapted to the new business environment.

Several sectors gained traction as Thailand recovered from the pandemic in the second half of 2021, including financial services, e-commerce, retail, telecommunications, media and technology (TMT), and renewable energy.

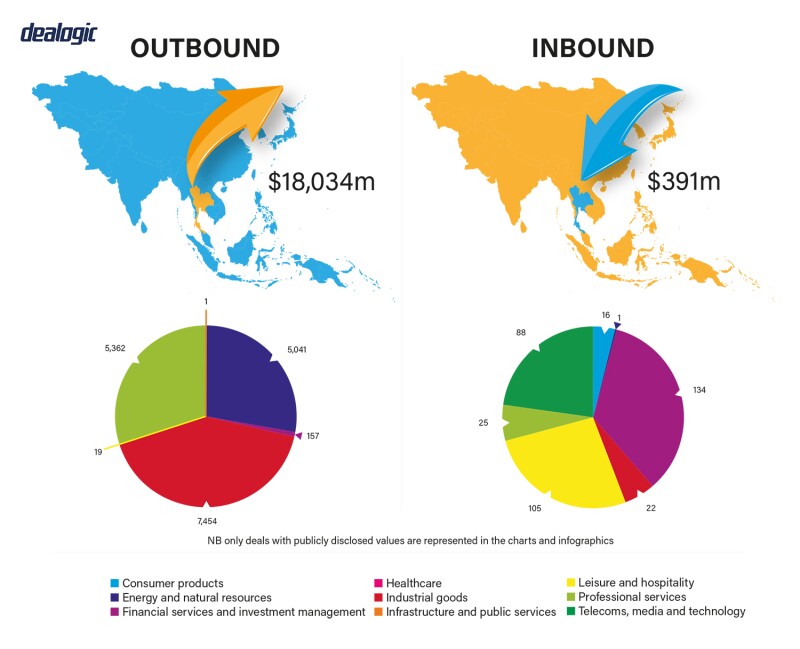

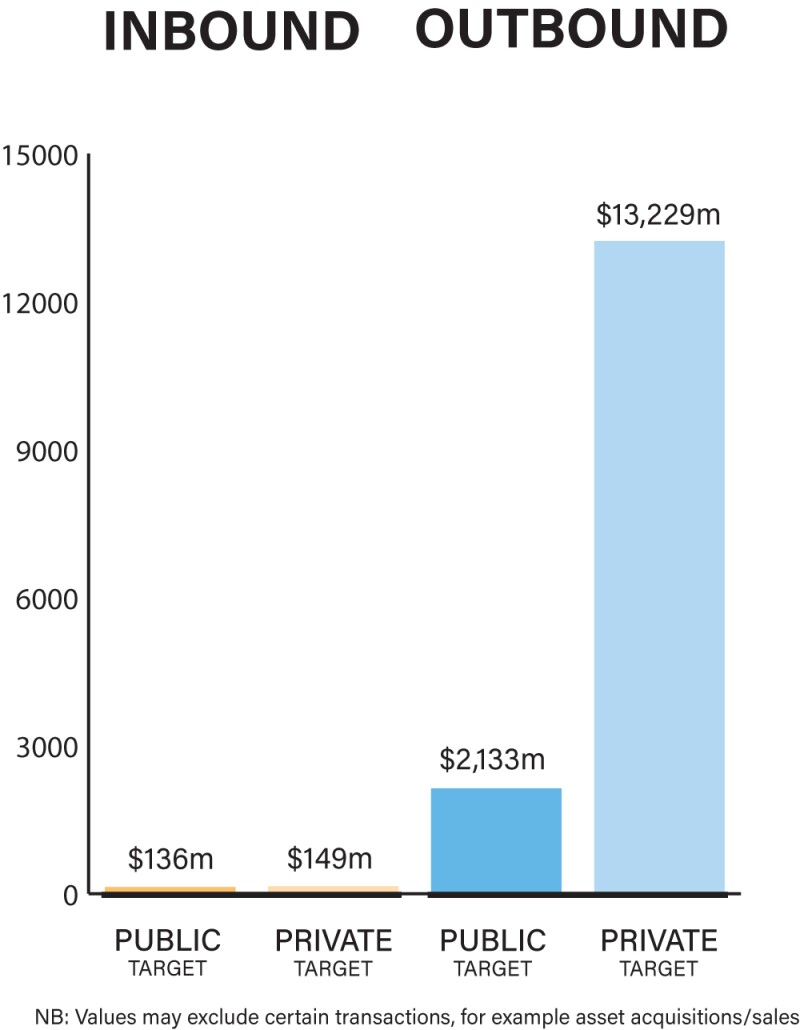

The Thai markets are driven by both private and public M&A transactions. While there has been an increase in public M&A deal volume, private M&A is more prevalent given that the target companies are mostly private companies and that the size of private M&A transactions are generally smaller than those of public M&A transactions, and are therefore more accessible to buyers. In addition, foreign buyers may be less inclined to invest in listed companies since the requirement for a mandatory tender offer can be triggered.

Public M&A transactions are often seen in relation to the financial services, TMT, logistics, renewable energy, infrastructure, and oil and gas sectors, as large-scale sellers and buyers are often involved. Private M&A is more active in the retail, food and beverage, and real estate sectors, given the form of legal vehicle and the size of business acquired.

Despite the Covid-19 pandemic, there have been a number of significant M&A transactions in Thailand in 2021, one of which was the proposed acquisition of 51% interest in Bitkub Online, a leading digital asset exchange and the latest unicorn in Thailand, by SCB Securities, a subsidiary of one of Thailand’s largest commercial banks, with a transaction value of approximately THB17.85 billion (approximately $540 million). This transaction is seen as a major development in the digital assets space, representing a milestone in Thailand’s digital economy infrastructure. It is anticipated that the digital assets space will continue to attract interest from both domestic and overseas investors, including existing players and financial institutions.

The other M&A transactions worth mentioning are the acquisition by Gulf Energy Development, one of Thailand’s biggest power producers, of a holding of shares (less than 50% but enough to make it the largest shareholder) in Intouch Holdings, which controls Thailand’s top mobile phone operator AIS, by way of a conditional voluntary tender offer, and the proposed merger between two telecom giants, namely True Corporation and Total Access Telecommunication. The latter has caused concerns regarding the impact on competition and consumers: at the time of writing, competition approval from the telecom regulator has not yet been obtained.

Economic recovery plans

M&A deal flow significantly picked up in 2021 compared to 2020 as many businesses have adjusted to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. Further, with an increase in vaccination rates and the easing of lockdown and travel restrictions, companies are more confident entering into M&A transactions. In addition, Thai listed companies have become more active overseas due to the need to search for strategic assets and/or partners and create synergies, particularly in the financial services, technology, and renewable energy sectors. Despite the easing of lockdown and travel restrictions in the second half of 2021, certain industries continue to be heavily affected, including hospitality, aviation, manufacturing, and real estate.

Despite the foregoing, the emergence of digital disruption has stimulated M&A deal flow in Thailand, particularly in the e-commerce, fintech, digital assets and technology sectors. Accordingly, companies are more willing to diversify their business portfolios to adapt to current business trends and provide greater synergies. Such investments are commonly entered into by way of joint ventures, venture capital investments or strategic collaborations, as these offer quicker and more efficient ways of penetrating other sectors.

In terms of deal structures in Thailand, there are many significant trends and factors influencing deal structures in Thailand, including purchase consideration, merger control clearance, synergies, and exit options.

|

|

“The Thai Cabinet approved an amendment to the amalgamation provision in the CCC to include the concept of ‘merger’ under Thai law” |

|

|

Fixed price remains the most common purchase price mechanism, as the parties desire to conclude the deal quickly and to avoid any adjustments pre- or post-completion amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

Proper antitrust analysis continued to play an important role in deal structuring in 2021 since the merger control regime has been fully enforced in the past few years. Merger control clearance is often included as part of the conditions precedent to completion. However, a ‘hell or high water’ clause remains very rare in Thai M&A transactions.

To help reduce investment risks and increase their ability to compete in a rapidly changing economy, many Thai conglomerates have started to invest in related businesses or new lines of business

(the so-called new s-curve), such as technology, e-commerce, e-payment, renewable energy, healthcare, and life sciences. In addition, the ability to exit either through a trade sale or an initial public offering (IPO) is becoming increasingly important for buyers investing in new lines of business or businesses that are growing exponentially such as start-up companies.

Since the impact of Covid-19 has delayed the timelines for M&A transactions, companies are now more than ever focused on getting the deal done as swiftly as possible by specifying clearer milestones with stricter completion dates. For example, the seller of a distressed target will attempt to close the deal at a faster pace by stipulating a clear timeline in the bidding requirements. Further, we have witnessed a sharp increase in the deal volume in certain industries that have been severely impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic such as insurance, food and beverage, entertainment, and hospitality.

Financial investors play an active role in shaping how M&A transactions are conducted in Thailand. The terms of M&A documentation are geared towards international practices, e.g., purchase price mechanisms, qualifications to warranties, limitation of liabilities and use of warranty and indemnity insurance. In addition, there is more focus on regulatory due diligence involving Thai target companies, particularly, anti-bribery and corruption, anti-money laundering, and data privacy aspects.

That said, private equity (PE) investors and venture capitalists are increasingly willing to take on minority interests alongside existing owners, especially in start-up companies in the financial, technology and healthcare sectors.

Legislation and policy changes

The key legislation governing private M&A transactions is the Civil and Commercial Code (CCC), with the Department of Business Development, Ministry of Commerce being the main regulatory body.

For public M&A transactions, the key legislation consists of the Public Limited Companies Act B.E. 2535 (1992) and the Securities and Exchange Act B.E. 2535 (1992) (SEC Act), including the rules and regulations issued thereunder, with the Office of the Securities and Exchange Commission of Thailand (SEC) and the Stock Exchange of Thailand being the main regulatory bodies.

In addition, the Office of the Trade Competition Commission of Thailand (OTCC) plays a significant role in monitoring merger control in Thailand, except for those sectors which are regulated by specific legislation such as telecommunications, broadcasting and television and energy. The Trade Competition Act BE 2560 (2017) (TCA) is the main legislation governing merger control in Thailand.

Specifically, the TCA aims to regulate mergers or acquisitions of businesses that may result in a monopoly, market dominance or substantial reduction of competition in a relevant market.

In December 2018, the merger control regime pursuant to the TCA came into effect. This has increased the complexity of M&A transactions in Thailand, especially in relation to deal structuring, timelines, certainty and documentation. A merger subject to the TCA may require a pre-merger approval or a post-merger notification.

A pre-merger approval is required where the merger would result in:

The creation of a monopoly, i.e. where there is only one business operator with absolute power to determine the price and supply of its products or services, and the business operator has a sales turnover of at least THB1 billion a year; or

A business operator being in a dominant market position, i.e. where (i) one business operator has a market share of 50% or more and a sales turnover of at least THB1 billion a year; or (ii) any top three business operators together have an aggregate market share of 75% (excluding any business operator which had a sales turnover of less than THB1 billion in the previous year or had a market share in the previous year of less than 10%).

A post-merger notification is required where the merger may result in a substantial reduction of competition in a relevant market, i.e. where the sales turnover of a business operator, or of all the business operators jointly conducting the merger, is THB1 billion or more, but does not lead to a monopoly or result in a business operator having dominant market power.

Full enforcement of the Personal Data Protection Act B.E. 2562 (2019) (which is deferred until June 1, 2022, due to the prolonged Covid-19 pandemic) is expected to have an impact on how businesses are conducted (especially in the financial services, insurance, retail and telecommunications sectors), disclosure of information for the purposes of M&A transactions, and areas of due diligence to be covered by the buyer.

Additionally, the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic has emphasised the importance of a material adverse change (MAC) clause in share purchase agreements. Parties have been paying greater attention to trigger events, carve-outs and the effects of the MAC clause. That said, in some cases (e.g., where the target business has been directly affected by the prolonged Covid-19 pandemic, such as manufacturing businesses), it is open to debate whether any event resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic should constitute a carve-out.

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors still have little impact on M&A transactions in Thailand due to the lack of understanding and importance given to them by the Thai government and various stakeholders. More discussions regarding ESG in M&A transactions in the energy sector – especially where international funds, international financial institutions and PE investors are involved – are expected soon.

As for another anticipated regulatory change, on June 26 2021, the Thai Cabinet approved an amendment to the amalgamation provision in the CCC to include the concept of ‘merger’ under Thai law (i.e. one of the merging entities will remain in existence following the merger). At present, the CCC only recognises business consolidation by way of amalgamation (i.e., two entities are combined, thereby creating a new separate legal entity). It is anticipated that this amendment to the CCC will become effective soon. This amendment will allow greater flexibility for business acquisitions and more tax-efficient M&A transactions in Thailand.

Market norms

While the concept of a nominee shareholder may be acceptable in certain jurisdictions, it is illegal for Thais to act as nominee shareholders to enable a foreigner to operate a business in circumvention or in violation of the foreign ownership restrictions under the Foreign Business Act B.E. 2542 (1999) or the Land Code. Given that nominee structures are often seen in Thai companies with different classes of shares, it is a common misconception that nominee structures are legally permissible and enforceable under Thai law.

The two areas about which questions are frequently asked when structuring an M&A transaction are foreign ownership restrictions, which apply to engagement in most businesses, and restrictions on land ownership by foreigners in Thailand. That said, not much attention has been given to the legal implications of the use of nominee structures as they can still be seen in certain industries such as real estate, tourism, agriculture and retail. Moreover, one area that is often overlooked is merger control clearance, as the TCA became fully effective relatively recently and parties are not yet completely familiar with the process.

Given the recent travel restrictions and social distancing requirements, most M&A deals have therefore been conducted remotely. The use of virtual data room platforms for due diligence processes and the conducting of board meetings and shareholders’ meetings via electronic means is also becoming more common in Thailand. In addition, the government authorities dealing with the registration of M&A deals, such as the Department of Business Development, Ministry of Commerce, are also moving towards e-application processes and e-appointment systems, rather than hard-copy documentation and physical meetings.

Despite these recent developments, it is worth noting that whilst electronic signatures are generally recognised under Thai law, they are not widely used in commercial transactions in Thailand. This is because the Thai authorities still prefer (and in most cases require) the use of wet-ink signatures for official documents such as forms and applications, and there are insufficient court rulings on the use of electronic signatures or other acceptable methods for creating legally effective electronic signatures under Thai law.

In practice, parties to commercial transactions still opt for wet-ink signatures when executing transaction documents or any important documents or instruments in order to avoid any future problems, should any party later attempt to challenge the authenticity of an electronic signature.

Public M&A

The key factors are the takeover rules issued under the SEC Act, which set out the requirements of a mandatory tender offer and a voluntary tender offer for the shares of a target company that is a listed company.

Firstly, the acquirer is required to make a mandatory tender offer where it has obtained shares in a quantity which reaches or exceeds the thresholds of 25%, 50% or 75% of the total voting rights of the target company. A mandatory tender offer also extends to cover an intermediate or the ultimate holding company which controls the target; this is known as the ‘chain principle’ rule.

In a mandatory tender offer, the acquirer must offer to buy all the shares and equity-linked securities of the target company, and such offer must not be conditional on a certain proportion of shareholders accepting the offer. On the other hand, a voluntary tender offer allows the offeror to announce the tender offer for all or a portion of the shares of the target company. The offeror may also set out a minimum percentage of shares the offeror wishes to buy in a voluntary tender offer.

Restrictions on foreign shareholdings are another important factor for both public and private M&A transactions in Thailand. This is because the Foreign Business Act B.E. 2542 (1999) prohibits a foreigner (e.g., a foreign entity or a Thai entity with 50% or more of its registered capital owned by foreigners) from conducting many types of business in Thailand. As such, a foreign investor may decide to make a partial tender offer for less than 50% of the target’s shares. In this regard, an approval of the shareholders’ meeting of the target company and the approval of the SEC must be obtained for the partial tender offer.

An unsolicited bid can be structured in a similar manner to a non-hostile bid, either through a mandatory or a voluntary tender offer. That said, due to a minority squeeze-out not being recognised under Thai law, hostile bids are not widely deployed in practice.

While the parties may set out conditions for a voluntary tender offer to take place, a mandatory tender offer is unconditional. The conditions for launching a voluntary tender offer usually include an approval from the relevant regulatory authority, an approval from the board of directors or shareholders of the offeror, and the relevant third-party consents before the tender offer can take place.

Similar to private M&A transactions, following the full enforcement of the merger control regime and the increasing number of high-profile public M&A transactions in Thailand in the last few years, more attention has been paid to merger clearance in voluntary tender offers. Additionally, a provision in relation to the MAC clause, in particular the outbreak of Covid-19, may also be included as a condition to the acquisition of the shares.

In addition, under Thai public takeover rules, the tender offer may generally be withdrawn when: (i) there is severe damage to the status or assets of the target company during the tender offer period which is not the result of an act of the offeror or an act for which it is responsible; or (ii) there is a material reduction in the securities value during the tender offer period which is caused by any frustrating action committed by the target company during the tender offer period, provided that these are stated in the tender documents and there is no objection raised by the SEC.

Break fees are not commonly employed in public M&A transactions in Thailand. Rather, public M&A deals are usually protected by non-refundable deposits or exclusivity undertakings in order to ensure protection for offerors. Nonetheless, when a break fee is adopted, Thai courts will award damages on an actual basis. This means that the quantum of the break fee can be adjusted at the court’s discretion.

Private M&A

The most frequently used consideration mechanisms in Thailand are fixed price and completion accounts. Although there has been an increase in the use of locked box mechanisms in recent years, they are still uncommon, especially following the outbreak of Covid-19, as the parties’ focus is now on concluding the deal and cashing in quickly, or the buyer usually wishes to be able to conduct a true-up exercise post-completion. The mechanisms of earn-outs and escrow arrangements are very rarely used.

While the use of warranty and indemnity insurance has increased in cross-border M&A transactions (especially where the seller is a PE investor), this is still uncommon for M&A transactions in Thailand, since the Thai parties are less familiar with the process, the associated costs are high, and these products have certain limitations, e.g. coverage exclusions and limitation of liabilities.

Apart from the MAC clause stated above, buyers usually request regulatory approvals required for the transaction and complete licences and permits that are material for the operation of the target business as conditions precedent to completion. In addition, merger control clearance is becoming more crucial at the structuring stage of deals, as the OTCC has been more active in recent years following the full enforcement of the merger control regime in Thailand.

It is common practice to adopt a foreign governing law in cross-border M&A transactions. The Thai courts generally recognise and uphold a contractual choice of foreign law, especially when one of the parties is foreign, subject to the usual reservations that it is not contrary to public order or the good morals of the people of Thailand, and such foreign law is proven to the satisfaction of the Thai courts to be suitable. Recognition of the foreign governing law would be less of an issue if a share purchase agreement governed by foreign law is enforced outside of Thailand, e.g. through a foreign arbitration or a foreign court.

The most common exits in Thailand are through trade sales and IPOs, which we usually find in private equity deals. Exit options (e.g., the right to trigger a trade sale or an IPO after the target business reaches the desired valuation) can be (and often are) included in a shareholders’ agreement.

Looking ahead

Given the expansive growth in the technology industry and the emergence of digital disruption in recent years, we anticipate that certain sectors – such as e-commerce, financial services, digital assets and TMT – will be more active than others. In addition, many businesses will search for opportunities to invest in related businesses or new lines of business and to build on their existing skills and expertise.

As for the legal industry, we have seen adaptation in legal practices, as many law firms are adopting artificial intelligence to help with their tasks, particularly in conducting due diligence and preparing legal documentation. Also, lawyers will embrace opportunities that arise from the transformation of their clients’ businesses and industries due to changes in technology and digitalisation.

Click here to read all the chapters from the IFLR M&A Report 2022

Vipavee Kaosala

Partner

Weerawong Chinnavat & Partners

T: + 666 5985 5779

Vipavee Kaosala is a partner in the firm’s M&A practice group. She has extensive experience in M&A and corporate finance, and advises financial institutions, multinational companies and PE houses on cross-border M&A, public takeovers, joint ventures, business reorganisations, foreign direct investments, securities-related transactions and regulatory issues relating to financial services.

Vipavee’s transactional experience covers a wide range of sectors, including finance, consumer goods and retail, manufacturing, insurance, healthcare and real estate. Her deal experience spans a number of south-east Asian jurisdictions, but with particular focus on Thailand.

Vipavee obtained a bachelor’s degree from Thammasat University, and an LLM degree in Corporate and Securities Laws from the London School of Economics. She is admitted to practice law in Thailand and England & Wales.

Siregran Sakuliampaiboon

Counsel

Weerawong Chinnavat & Partners

T: + 669 0982 2602

Siregran Sakuliampaiboon is a counsel in the M&A practice group. She specialises in M&A, , corporate structuring and corporate management and control, focusing on cross-border transactions.

Siregran obtained a bachelor’s degree from Chulalongkorn University, an LLM degree in Commercial Law from the University of Cambridge, and an LLM degree in taxation law from the London School of Economics.

Akeviboon Rungreungthanya

Senior associate

Weerawong Chinnavat & Partners

T: +668 9049 3399

E: akeviboon.r@weerawongcp.com

Akeviboon Rungreungthanya is a senior associate in the M&A practice group. He has extensive experience working with private and public companies, from SMEs to multinationals, and provides solutions-based advice.

Akeviboon advises on domestic and cross-border transactions, foreign direct investment, and corporate-commercial matters in a wide variety of sectors.

Akeviboon obtained a bachelor’s degree from Chulalongkorn University, and an LLM degree in International Business Law from University of London (School of Oriental and African Studies).