The urgency for climate action was highlighted on the international stage during the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow in November 2021. One of the key announcements was made by a group of 450 financial institutions, managing more than $130 trillion in total assets, equivalent to 40% of global private wealth.

This coalition, the UN Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), comprises banks, insurers and asset managers across 45 countries. It aims to expand and accelerate net zero ambitions and efforts across the financial services sector and other industries to achieve the targets of the Paris Climate Agreement by limiting global temperature increases to 1.5°C from pre-industrial levels.

This announcement represents a fundamental shift from traditional investment approaches where environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors were overlooked in informing investment decisions. It also signals to the private sector that major financial institutions will play a critical role to go beyond the principles of responsible investing, and that the incorporation of ESG issues alone is no longer sufficient. A more holistic approach to set and achieve ambitious net zero targets is required.

Consequently, it is more important than ever for the international community to collaborate on a globally recognised sustainable finance taxonomy that explicitly defines and classifies sustainable economic investments and works to reduce and prevent greenwashing practices.

A globally recognised taxonomy can provide financial institutions with decision-useful information relating to investments in sustainable economic activities and can ultimately support institutional investors with decarbonisation and net zero implementation across their investment portfolios.

Indonesia’s Green Taxonomy

Recognising the importance of a sustainable finance taxonomy, in January this year President Joko Widodo launched Indonesia’s Green Taxonomy at the 2022 Financial Services Industry Annual Meeting (Pertemuan Tahunan Industri Jasa Keuangan). This builds on the government’s efforts to attract more capital towards sustainable finance in Indonesia.

The Green Taxonomy aims to classify sustainable financing and investment activities and is intended to be the basis for all stakeholders carrying out sustainable economic activities. It further classifies activities that support environmental protection and management and climate change mitigation and adaptation in line with the government’s Nationally Determined Contributions, with the goal of encouraging innovation and investments in sustainable economic activities.

Indonesia’s Green Taxonomy is one of the first policy attempts to encourage the private sector to prioritise green investments and further incentivise businesses to comply with ESG-related regulation that can otherwise become barriers to accessing sustainable finance.

Prior to the launch of the Green Taxonomy, the Indonesian Financial Services Authority (OJK) developed the Sustainable Finance Roadmap Phase II (2021-2025) to accelerate the sustainable transformation of the financial services sector. The roadmap serves as a blueprint for the future of Indonesia’s financial sector, and prioritises action in seven key areas: policymaking, products, market infrastructure, national coordination, non-governmental support, human resources and awareness building.

In enabling the financial services sector to become more competitive and resilient to environmental and social risks, OJK intends to integrate ESG further into risk management by introducing more rigorous ESG reporting requirements, developing key performance indicators and building human resource capacity (see OJK’s Sustainable Finance Roadmap Phase II (2021-2025).

Globally, there is an increasing demand from regulators, businesses, and the wider public for financial products that incorporate ESG. Moreover, with nearly 5,000 Principles of Responsible Investing (PRI) signatories, investment managers and asset owners have also committed themselves to incorporating ESG into investment analysis, decisions, policies, practices and disclosures.

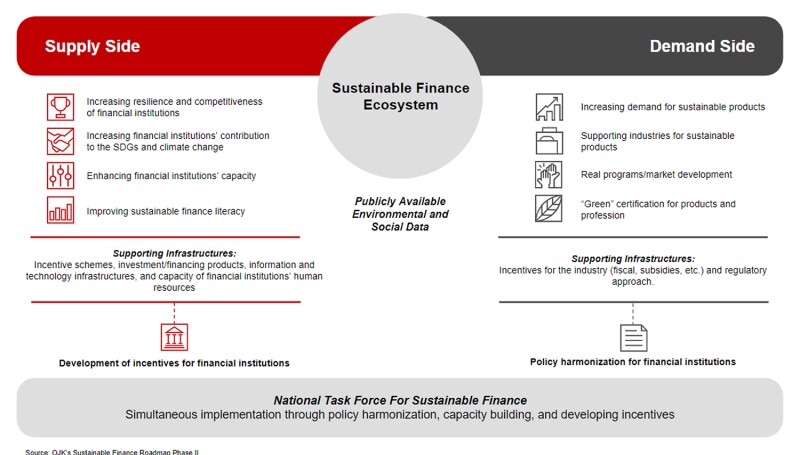

In Indonesia, there have been similar trends, and as OJK works to expand sustainable finance regulations and incentives, its efforts will likely affect both supply and demand in the financial services sector. OJK’s roadmap aims to develop new incentives for financial institutions while harmonising the regulatory framework that applies to them. The figure below presents an overview of the Indonesian sustainable finance ecosystem and the government’s priorities for the National Task Force for Sustainable Finance.

In addition to the government’s efforts, investors are the primary drivers for the growing interest around ESG and ESG value creation in Indonesia. More and more, investors look for ESG strategies, net zero commitments, emissions reduction strategies and comprehensive disclosures and reporting practices to inform their investment decisions.

With the emergence of the Green Taxonomy, and as OJK continues to build on this first version of the Taxonomy, investors may increasingly refer to the Taxonomy to increase their sustainable investments, reduce their emissions across their portfolios and ultimately work to achieve net zero.

In the current version of the Taxonomy, 2,733 sectors and sub-sectors were studied, of which 919 were mapped to sub-sectors, groups or business activities in line with level 5 of the Indonesian Standard for Industrial Classification (KBLI 5). (Indonesia’s Central Bureau of Statistics classifies business activities using a five-level classification system, with level 1 being the most general and level 5 being the most specific.)

The Green Taxonomy divides sectors and sub-sectors into three categories: green (does no significant harm, applies minimum safeguards, has a positive impact on the environment, and aligns with the environmental objective of the taxonomy; yellow (does no significant harm); and red (harmful activities). Of the 919 sectors and sub-sectors, only 15 have so far been classified as green (The Green Taxonomy divides sectors and sub-sectors into three categories, namely: green (does no significant harm, applies minimum safeguards, has a positive impact on the environment, and aligns with the environmental objective of the taxonomy, yellow (does no significant harm), and red (harmful activities).

According to the Taxonomy, the remaining 904 sectors and sub-sectors could not meet the government’s prerequisites for green classification. If institutional investors increasingly invest in sustainable economic activities, the Green Taxonomy, although now voluntary, may gain more traction over the coming years, which can lead to non-green sectors and sub-sectors observing a decline in investor appetite, especially from long-term investors.

It is therefore imperative for the sectors to consider comprehensive ESG action to decarbonise and work towards science-based net zero targets, especially across industries that are not inherently carbon intensive.

Climate-related risks and opportunities

As Indonesian companies look to start their ESG journey and take comprehensive action across industries, it is imperative that they take a holistic and long-term value creation approach in line with their wider stakeholders’ expectations, including institutional investors.

Although the Green Taxonomy aims to attract more investment towards sustainable economic activities, the primary purpose of the Taxonomy is to support financial institutions to better understand and distinguish green and sustainable economic activities from those that do not contribute significantly to advancing climate action and environmental protection. Consequently, the Taxonomy on its own is not likely to dissuade investors from investing in non-green categories.

|

|

“It is imperative that Indonesian companies take a holistic and long-term value creation approach in line with their wider stakeholders’ expectations, including institutional invest” |

|

|

However, with the growing focus on net zero and the emergence of groups such as GFANZ, there is a clear indication that the global market will focus increasingly on accelerating climate action and invest in sustainable economic activities. Having this recognition can enable company boards and C-suites to call for drastic action to prevent value erosion. More visionary companies will not settle for regulatory compliance and minimal effort to preserve their value; rather, they will thoroughly investigate ESG issues across the value chain to identify ESG risks and opportunities that can enable them to create long-term value.

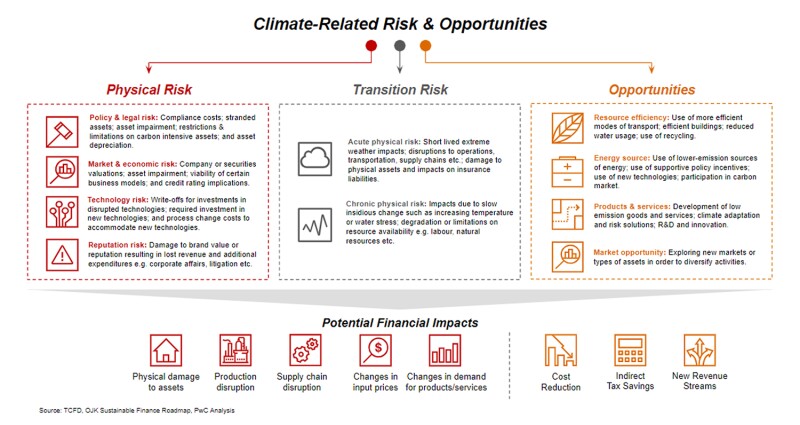

In order to understand how a lack of focus and inaction can lead to value erosion, it is critical to understand the two types of climate risks to which companies are exposed. These are physical and transition risks.

Physical risks are climate-related risks that arise from the physical impacts of climate change and environmental degradation. As defined by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), there are two main types of physical risk: acute and chronic. Acute physical risks refer to short-lived extreme weather impacts; disruptions to operations, transportation, supply chains; damage to physical assets and impacts on insurance liabilities. Chronic physical risks refer to impacts due to slow insidious change such as rising temperatures or water scarcity; degradation or limitations on resource availability, such as labour and natural resources.

Transition risks refer to risks that markets and industries face as a result of changing strategies, policies, and investment appetite in order to reduce the negative impacts on the climate. In line with TCFD guidelines, there are four primary transition risks: policy and regulatory risks, market and economic risks, technology risks and reputational risk. Policy and regulatory risks refer to compliance costs, stranded assets, asset impairment, restrictions and limitations on carbon-intensive assets and asset depreciation. Market and economic risks refer to company or securities valuations, asset impairment, viability of clean business models, and credit rating implications. Technology risks refer to write-offs for investments in disrupted technologies, required investment in modern technologies and process change costs to accommodate those new technologies. Finally, reputational risk refers to lost revenue and other related expense due to damages to the brand or company reputation arising from litigation, corporate affairs and other related events.

Understanding these climate-related risks can enable companies to develop ESG strategies, integrated with the corporate strategy, that can propose risk management and mitigation measures and identify commercial opportunities that can positively affect financial performance and the balance sheet.

Some of these opportunities include resource efficiency, energy transition, sustainable products and services and new market opportunities classified as green. The potential financial impacts of these opportunities can be observed in various ways, including new revenue streams from green business models, cost reduction across the value chain and indirect tax savings such as carbon tax. The figure below provides an overview of these climate-related risks and opportunities.

Creating value and responding to investor demands

Once companies have a deeper understanding of the risks and opportunities facing their market, industry and geography across the supply chain, they are in a strategic position to optimise value creation through ESG factors and considerations. The value creation journey can be broken down into six practical steps that companies can take to affect company value. These comprise the development of an ESG/sustainability strategy, net zero strategy, reporting strategy, sustainability reporting, ESG rating and effective dissemination.

Companies can develop ESG strategies that would determine the Board’s and company’s sustainability vision, targets and rationale, and identify alignment to the overall corporate strategy. The strategy can also prepare a roadmap in terms of the overall plans, objectives and milestones over a period of two to three years that are to be undertaken and achieved. Furthermore, the strategy will align ongoing sustainability-related initiatives and propose new initiatives that are critical to achieving the identified targets.

Once the company has an ESG strategy that addresses key considerations under E, S, and G, the company can refer to the strategy to focus more specifically on addressing climate-related risks and opportunities in the market. At this stage, the company can identify a comprehensive emissions reduction strategy, at a minimum, or more ambitiously commit to net zero science-based targets, or even more ambitiously than that, plan to become a net positive business.

Greenhouse gas emissions from a business activity can be classified into three scopes: scope 1 (direct emissions from company-owned assets); scope 2 (indirect emissions from the generation of purchased energy); and scope 3 (all indirect emissions not included in scope 2 that occur across the value chain of the company, including upstream and downstream emissions). The emissions reduction focus will identify areas of opportunity for reducing greenhouse gas emissions across scopes 1, 2, and 3 (GHG emissions from a business activity can be classified into three scopes: (i) Scope 1: direct emissions from company-owned assets, (ii) Scope 2: Indirect emissions from the generation of purchased energy, and (iii) Scope 3: All indirect emissions not included in Scope 2 that occur across the value chain of the company, including upstream and downstream emissions).

Beyond emissions reduction, the company can identify business opportunities that can move the company into green classified sectors and sub-sectors. Finally, the company can also rely on the carbon market to better assess and calculate the investment needed to achieve carbon neutrality, as a start, and ultimately its net zero targets.

From there, a reporting strategy identifies key stakeholders, their requirements, regulatory frameworks, ESG ratings, databases needed for comprehensive reporting and ESG standards and frameworks most applicable to the company’s needs. This strategy is followed by the preparation of the sustainability report and disclosures needed for relevant stakeholders. Once a company has published its sustainability report and disclosed ESG-related information to its shareholders, investors and others as needed, the company is strategically positioned to receive an ESG rating from a rating agency.

In Indonesia, there are four ESG indices on the Indonesian Stock Exchange (IDX). Three of them were developed by the Kehati Foundation in partnership with IDX (SRI-Kehati, ESG Sector Leaders IDX Kehati, and ESG Quality 45 IDX Kehati), while the other is a partnership between IDX and Sustainalytics (IDX ESG Leaders).

Obtaining ESG ratings, even on a voluntary basis, can provide investors with more information that could inform their investment decisions. Finally, how a company chooses to disseminate all this information, from ESG strategy to ESG ratings, will be critical to build stakeholder confidence in the company’s ESG performance and overall value. The figure below presents an overview of these six steps, which is intended to be a descriptive illustration of the different actions that can be considered, but each company’s value creation journey may be slightly different.

As part of the above value creation journey, Indonesian companies should also take into account international and Indonesia-specific certifications, including industry-specific certifications, which would signal to the market the company’s ESG commitment and actions. Examples include the Ministry of Environment and Forestry’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction Certification, Company Performance and Management Rating Assessment Programme and the Ministry of Agriculture’s Indonesia Sustainable Palm Oil certification.

Towards a global taxonomy

Globally there is a strong foundation for ESG investing and financial institutions have built on this momentum by indicating their collective commitment to sustainable finance and net zero.

If there are no major political or economic disruptions in the global market, demand for sustainable finance products will continue to rise as more companies attempt to align their vision and corporate strategy with investor expectations and appetite. Moreover, in the coming years, there is an expectation that a globally recognised sustainable finance taxonomy will be developed with national taxonomies supplementing and contextualising the global taxonomy for local markets.

Regardless of regulatory developments at the global or national level, companies should not wait before incorporating ESG into their strategies and operations. ESG investing is not about highlighting or promoting corporate social responsibility; rather, it has direct and indirect financial implications on a company’s financial performance and overall value. Therefore, it is imperative that companies treat it with the appropriate mindset that manages and mitigates ESG risks, while also identifying business growth opportunities.

Click here to read all the chapters from IFLR ESG Asia Report 2022

Fifiek Mulyana

Director

PwC Indonesia

T: +62 21 509 92901

Fifiek Mulyana is a Junior Partner (Director level) at Melli Darsa & Co (MDC). Fifiek has more than 20 years of extensive experience specializing in government and public sector projects. She has been involved in developing regulatory and organization frameworks for government, donors (such as AUSAID, ITDP, GIZ) and state-owned enterprises, namely the Government of Jakarta, PT Kereta Api Indonesia (Persero) and PT Transportasi Jakarta. Fifiek leads the ESG services at MDC. She is also active in speaking at PwC Thought Leaderships on the legal aspects of ESG, specially the most recent carbon pricing regulations and the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil certification.

Fifiek obtained her Bachelor’s Degree in Law from University of Indonesia and Master of Law (LL.M) from Northwestern University, Chicago, USA. She is admitted to practice in Indonesia. She has registered and obtained an advocate license from Indonesian Bar Association (PERADI).

Maurice Shawndefar

ESG adviser

PwC Indonesia

T: +62 21 5099 2901

Maurice Shawndefar is a public policy and ESG specialist with experience in the private and non-profit sectors.

Maurice specialises in international development with a focus on sustainable development policies. He has 11 years of professional experience with more than six years as a sustainable development policy specialist in Indonesia. He advises governments, international development agencies and businesses on sustainability policies and strategies to incorporate into national priorities and programmes or corporate strategies. He has managed projects relating to the SDGs, sustainable finance and sustainable consumption.

Maurice is a graduate of the University of California, San Diego and the Hertie School of Governance. Prior to joining PwC, he was a sustainable urban development specialist at the United Nations Development Programme in Indonesia.